Two white Americans telling a story from an Asian perspective might ring alarm bells for some nowadays. Investigating Western Imperialism, with the arrival of a military presence to an isolated Japan in 1853, is tricky. But, surely, the first point in favour of this revival of Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman’s musical is that you’re going to have to think. The work is as challenging as it was when it débuted in 1976, maybe more so.

It turns out that in skilful hands the project works… for the most part. The casting is sensitive. Indeed, this is a co-production with the Umeda Arts Theatre in Japan. There are clichés about the country and the history is whistle-stop, but it should be noted that the show has been updated, with additional material by Hugh Wheeler. Attempts at humour are limited (and excellent, by the way, ‘Please Hello’ is an erudite highlight). Two numbers that deal with sex – both showing violence toward women – make a powerful, disturbing pairing. Nonetheless, it all feels slim.

Director Matthew White’s brilliant staging is a triumph of minimalism, and the show looks amazing. Paul Farnsworth’s set, Ayako Maeda’s costumes and Paul Pyant’s lighting are all gorgeous. And there’s Ashley Nottingham’s choreography, with You-Ri Yamanaka credited as a cultural consultant – the way the cast moves is fascinating, and every action in the show is carefully curated. Could all this almost be a problem? Could the aesthetics be fetishistic: the idea of Japan (that Empire of Signs) can be intoxicating. Maybe you’d counter by saying the idea is potent for nations all over the world. White is certainly overt about the idea of presenting the past like a museum display.

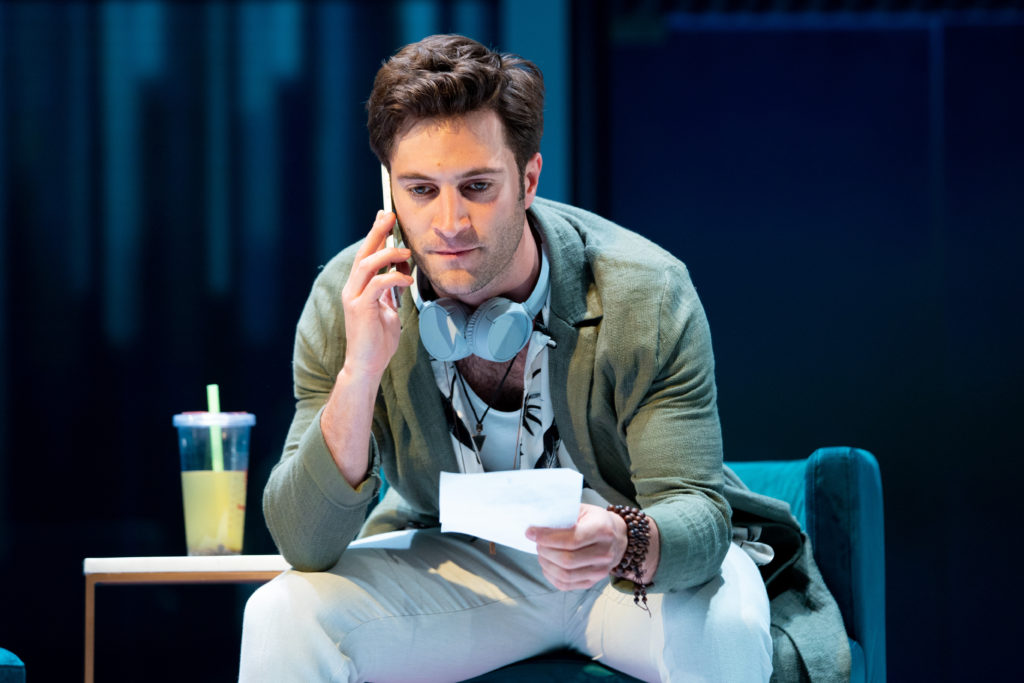

It isn’t fair to say Sondheim, Weidman or White paint broad strokes when they are also precise. But a lot of ground is covered very quickly (the show is short). A saving grace comes with something surprisingly old-fashioned – the characters. A trio focus drama and emotion. There’s Kayama, a samurai given the thankless task of dealing with the unwelcome Americans, and his wife, Tamate, who have a brief but beautiful romantic number and tragic story. Takuro Ohno and Kanako Nakano give exquisite performances in the roles. Afterwards, Kayama’s friendship with Manjiro, a strong role for rising star Joaquin Pedro Valdes, reflects responses to cultural change in an easy manner. And John Chew also deserves praise as the narrator who anchors the show – although his role’s transformation into Emperor Meiji is the book’s poorest move.

Unusually for a Sondheim piece, consideration of his music and lyrics is delayed – there is so much else to bear in mind. There are brilliant songs in Pacific Overtures, the lyrics are a model of efficiency as smart as you’d expect. The score was innovative in 1976 and stands out just as much now. The show is a must for fans – it doesn’t come around that often – and this is as fine a production as I can imagine. Still, for most, the evening is probably more interesting than enjoyable, its brevity being a problem that makes it an overture rather than a complete work.

Until 24 February 2024

www.menierchocolatefactory.com

Photos by Manuel Harlan