While it’s difficult to define a work as deep as David Ireland’s 2017 play, currently being shown on YouTube with a request for donations, it’s easy to say that this thought-provoking comedy horror is something everyone should see.

It’s framed around the clinical treatment of Eric, a dour and obsessive Northern Irish protestant whose psychosis is at first amusing – he believes his grand-daughter is IRA politician Gerry Adams! Up until what Eric has done becomes clear, the play is full of belly laughs. Stephen Rea makes a masterclass of this starring role, with a magnificent, deadpan delivery.

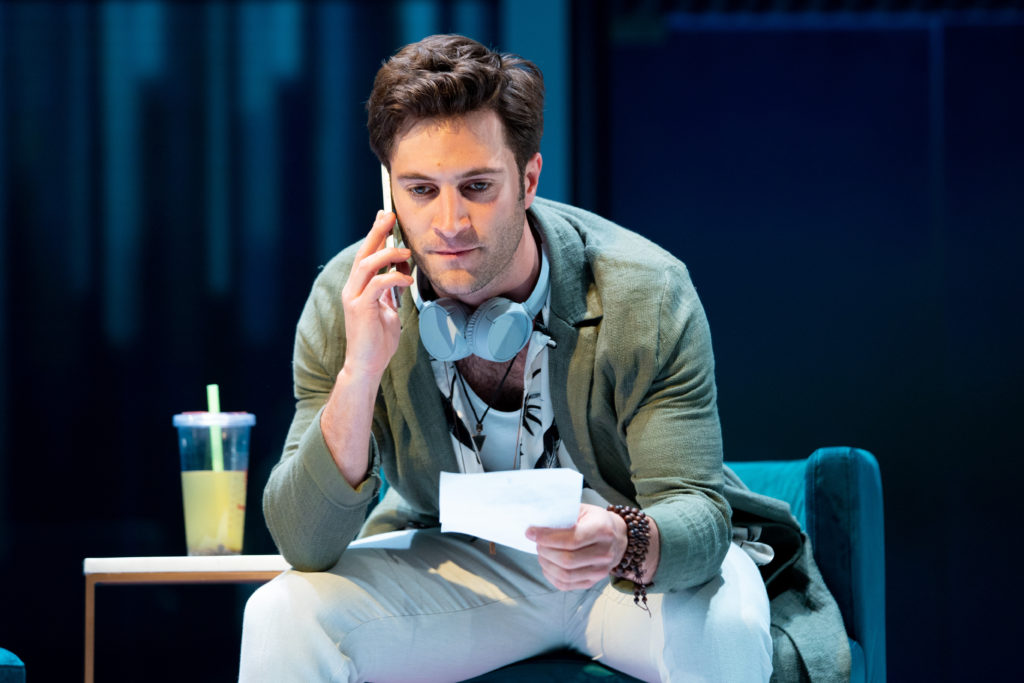

Following the play’s descent into darkness, Eric is accompanied in his treatment by two very different kinds of therapists… one of whom isn’t even real. First up, Ronkẹ Adékoluẹjo makes a calm and clear psychologist convincing – it’s a performance that grounds the play. Then comes Chris Corrigan, also superb, who plays a gun-toting paramilitary-turned-mindfulness guru – and film critic – whose role shows how mad things are becoming.

Plays don’t get much funnier than Cyprus Avenue, especially not when they deal with murder, mental illness and racism. But theatre also doesn’t get much more disturbing. Be prepared, as the final scenes are grotesque, shocking and traumatic.

What the jokes and drama have in common is Ireland’s intelligence and sense of purpose. Examining both sectarianism and racism, and the way prejudice links the two, brings up big questions in a challenging manner. The play is preoccupied with time – past, present and future – to show how each has a distinct impact on self-identity. And Ireland has a firm handle on how disturbing the disturbed can be. Eric’s breakdown devastates his family long before he physically hurts them – a fact carefully acknowledged in the moving performances from Andrea Irvine and Amy Molly as, respectively, his wife and daughter.

That the final scenes are so awful, with Rea transformed into a terrifying figure, confirms director Vicky Featherstone’s bold vision for the piece. Yes, the mood changes dramatically. But this comes with an insidious, sinking feeling that builds carefully. Eric’s crazed logic brings about a brutality that is impossible to predict in its extremity. Yet the idea that such consequences follow his demented reasoning, arguments we’ve been laughing at so hard, provides a powerful point to end on.

Available until the 26 April 2020 from https://royalcourttheatre.com/whats-on/cyprus-avenue-film/

Photos by Ros Kavanagh