Welcome as the recorded shows helping theatre-lovers on lockdown are, a live stream is a lot closer to what we really love. It’s exciting even to wait for something to happen, let alone watch in real time. Albeit a brief half hour show, labelled a reading rather than a performance, this offering from the Remote Read project is warmly welcome.

The choice of Tom Stoppard’s short, from 1964, shows itself as appropriate to our current situation gradually – it’s about a man who wants to do nothing. Arriving at the “A1” Beachwood Nursing Home, willing to pay to stay, Mr Brown wants “privacy and clean linen” in his search for a safe space. Stoppard develops a mystery, then a romance, and his patient with patience intrigues throughout.

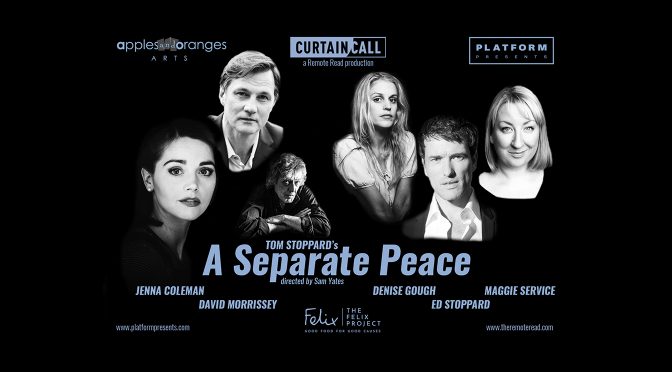

There’s a lot of talent – working remotely, remember – to bring out the best in the piece. Director Sam Yates has done an excellent job with a starry cast. David Morrissey takes the lead as the “likeable” Brown, bringing out a lovely humour with suitably gnomic remarks working hard. Denise Gough introduces considerable tension as a Doctor trying to work out what is going on, with Ed Stoppard as the vaguely exasperated Matron. A subtle love interest with young nurse Maggie, played by Jenna Coleman, is made tender and touching. Coleman and Morrissey build up a great sense of togetherness – all the more remarkable when you remember they aren’t in the same room.

It is still hard to forget this is a Zoom meeting, no matter how different it is from one you’d have for work. Performing against a white background isn’t without problems, and I’d like to know if the number of screens viewers are shown can be controlled better. But these are mere technical glitches, and the storytelling in the show undoubtedly works. Behind the questions of Brown being “a crook or a lunatic”, which Yates allows to be explored so well, he is a challenging figure. Stoppard leaves open suggestions of background trauma, such that his character retains an air of enigma. Brown’s search for peace makes him something of a mystery, and hugely suited to puzzling over under imposed isolation.