Congratulations to Iris Theatre, which celebrates ten years of its summer season at ‘The Actors’ Church’. For 2018 its family show, The Three Musketeers, starts on 2 August, while its annual Shakespeare offering is the story of Prospero wielding his magical powers to reclaim his usurped Dukedom. The production shows the company’s strengths: accessible, solidly crafted, engaging shows that fully exploit this venue’s charms.

It is laudable that a decade on director Daniel Winder still wants a challenge: The Tempest is a tricky text with a lot of ink spilt over it. The play’s oddities aren’t shied away from here; programme notes suggest it’s a response by Shakespeare to court masques, those peculiar entertainments designed by Inigo Jones, who also built St Paul’s. But what seems serendipitous on paper isn’t elevated on to the stage: the masque within the play, performed inside the magnificent church, is too far from the “majestic vision” described.

There are other problems, too. Anna Sances’ costume designs are intelligent but need more budget in execution. Candida Caldicot’s musical compositions are good, the cast’s vocals superb, but background music (and noises) are an odd, sometimes overpowering, mix.

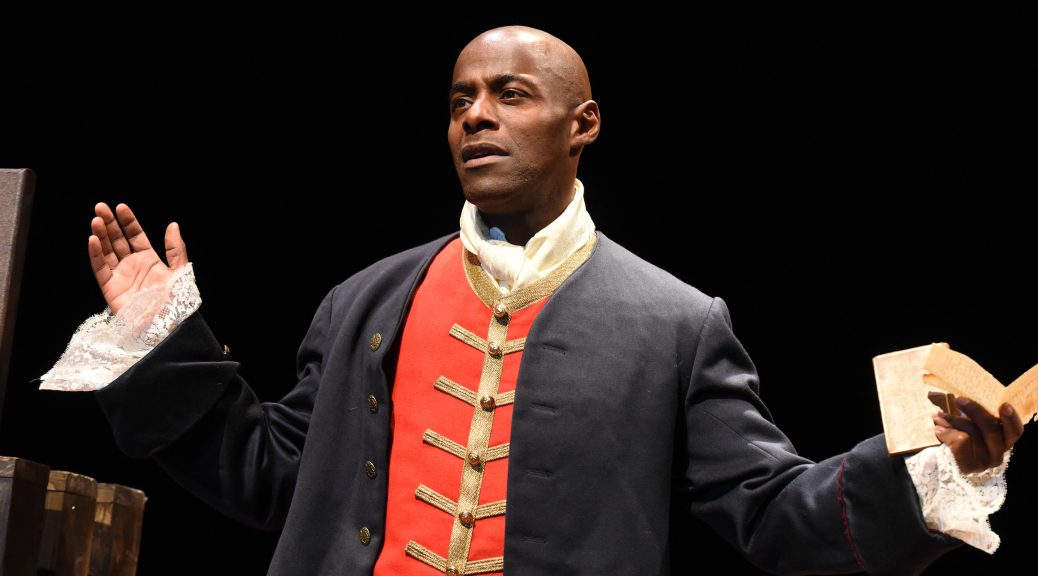

Flashy touches thankfully don’t detract from the production’s strong base. Winder knows what he is doing and gets a huge amount from his small cast. There are only seven performers here – acting their hearts out – and, if there are mixed results a lot of the blame rests with the comedy. There’s a sound effort made by Paul Brendan and Reginald Edwards in the roles of drunken Trinculo and Stephano, but I’ve never seen the scenes get that many laughs. There is strong work from Prince Plockey as Caliban and a particularly impressive Antonio.

Underpinning the show is a classy performance from Jamie Newall as Prospero, who is a joy to hear. But the evening belongs to Charlotte Christensen as Ariel. With her total commitment to the role, alongside a stunning singing voice, Christensen brings out a sense of wonder and sensitive confusion. There is a quality of fragility and questioning, as well as power that is lacking in the rest of the production. Nonetheless, while Winder’s ambition doesn’t always pay off, his confident show safely pulls through.

Until 28 July 2018

Photo by Nick Rutter