Howard Brenton’s long engagement with the master playwright August Strindberg has proved thoughtful and fruitful, with results here that are spectacular. No stranger to controversy in his own plays, Brenton is almost contrarian in his respect for his predecessor. And presenting Strindberg’s tale of a mistress who has an affair with her father’s valet so simply, with no burdening concept or take on the text to push, is a mark of confidence in the original that allows it to both shine and shock.

The direction from Tom Littler is masterful. With some boldly slow pacing that enforces naturalism and an impressive attention to detail, the play is gripping from the start. We first see the aristocratic household’s cook, Kristin, about her chores and waiting on that valet, Jean, who is also her fiancé. Establishing character through mundane actions is one of those things they teach you are drama school isn’t it? But I’ve seldom seen it done with more success that Dorothea Myer-Bennett’s efforts here. Based on the smallest gestures, the character fascinates, carefully becoming a complex and ultimately triumphant figure. Myer-Bennett’s close study pays off marvellously.

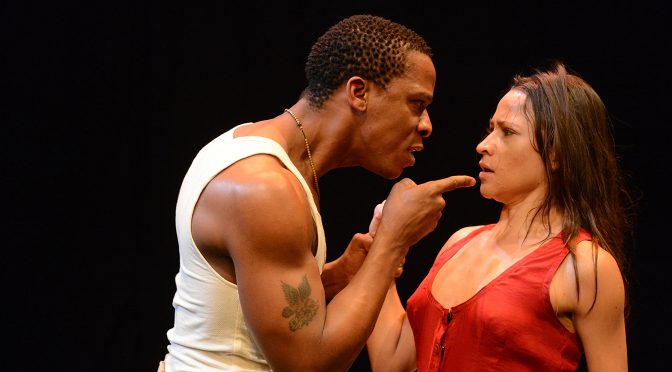

Along the way, we have the drama of Jean’s one-night stand with Julie. It is to Brenton’s credit that both get equal focus, aiding the theme of class conflict that powers his version and reflects Strindberg’s troubled relationships with women. The performances from Charlotte Hamblin and James Sheldon are excellent as they take us through Strindberg’s “serious game” of seduction with such precision. Sheldon works magic with his mercurial character, hot with anger and coldly rational by turns. And Hamblin is a true star in the title role, building Miss Julie’s mental instability for the first half, then going all out to become frightening and pitiful in equal measure.

Let’s not forget the importance of sexual chemistry – this is an erotic show and, as a mark of how smoothly Littler handles the twisted kinks, little skin is on show. It is also testament to the exactitude of the production that Kristin and Jean are such a believable couple: the shared cigarette or help with a bow tie become captivating touches. Their relationship raises the stakes and makes Julie’s plans for escape all the more fantastical. The mix of misandry and self-loathing from our heroine becomes increasingly uncomfortable in the small, one-room world Littler brings to life. It’s always an effort for a modern audience to appreciate the shame of a ‘fallen’ woman, so Brenton’s skill lies in showing this a play about more than sexual politics. And his triumph comes in making Miss Julie’s actions seem radical and tragic once more.

Playing in repertory with Howard Brenton’s version of Creditors until 1 June 2019