Robert O’Hara’s semi-autobiographical play is original and adventurous. To say Bootycandy is the story of a gay African American boy growing up in the 1980s belies how many surprises the show has. This is theatre that takes huge risks, crediting its audience with intelligence, and confident in its meta-theatricality.

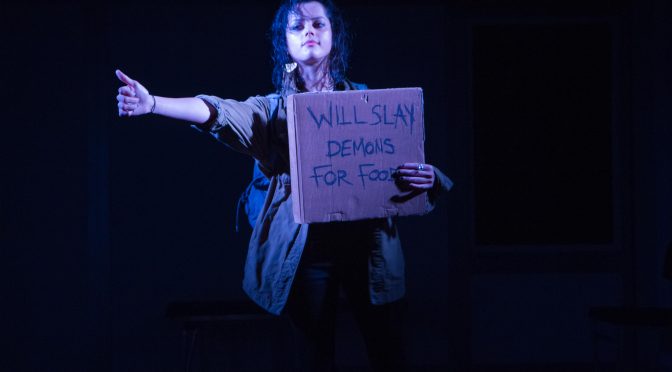

Veering wildly from scene to scene, concessions to a conventional story come with the character of Sutter and his family. Sutter’s growth is literal – he first appears as a small boy and becomes an increasingly central, and powerful, figure. Taking the role, Prince Kundai impresses throughout.

Nonetheless, presented as a collection of sketches – or maybe memories – there is the danger of the piece being disjointed and confusing. Credit to director Tristan Fynn-Aiduenu, who ensures a coherent atmosphere. And, thankfully, every strangely isolated scene is superb – give each a star and the rating for this show would be off the scale.

A scene of women talking on the phone is a highlight for Bimpé Pacheco and DK Fashola, Luke Wilson’s drag queen pastor is superb and a monologue for Roly Botha truly extraordinary. These are tremendous performances, each aided by Malik Nashad Sharpe’s superb work as director of movement. Dance is integral to Bootycandy: the physicality – at every moment – is enthralling.

A queer ‘lens’ here is flipped as O’Hara examines his community and Sutter’s interactions with a heterosexual world. The play’s most vivid characters are women (a mother and grandmother). And there is a fixation with straight men that gets very dark indeed.

The scenes are funny, sexy, and scary – sometimes all three at the same time. And none of this is as it first seems. It’s possible what we are watching is a collection of ‘works in progress’ by playwrights at a conference. So, is Bootycandy being constructed before our eyes? Even the cast starts to question what on earth is going on!

There isn’t one key to the undoubtable success of this show – why would there be when we are presented with so many ideas and perspectives? But Fynn-Aiduenu creates an impression of spontaneity that works to great effect, generating a tremendous energy that powers the show and ensures Bootycandy hits a sweet spot.

Until 11 March 2023

Photos by Ali Wright