If you are going to base a musical on a true story, it makes sense to choose an incredible one. Jill Santoriello, Jason Huza and Jeremiah James, who co-wrote the book for this new show, picked the you-couldn’t-make-it-up story of Count Carl von Casel. Shipwrecked off Cuba, although unqualified he treated a young girl for tuberculosis, dug her up after she died, “married” her, then lived with her body for seven years. At her request. You really can try to make a show out of anything and the result of such bravado here is intriguingly insane and often entertaining.

Santoriello’s score makes us, for the most part, forget how icky the whole thing is. But the unashamed romanticism of the music, while pleasant, makes the love affair a little dull. And very old fashioned. The piece may start in the 1930s but with such an off-beat story you might expect more musical quirks – such a crazy tale needs to be madder overall. When it comes to the comic implications of the scenario, the show gets better (and the lyrics, by Santoriello with Huza, improve immeasurably). There are several jolly moments and even some jazz hands.

It’s an irony that the show doesn’t have enough life. Several subplots appear and are killed off: a scientific rival for the Count and a mercenary sister for his love – throw ‘em a song please. While a tight-knit community is part of the plot, there’s little sense of the titular location. Frustratingly, a device is present – a group of local troubadours – but isn’t exploited enough. The celebrity that Von Casel suffers upon exposure, with locals seeing the chance to make money from the story, is a highlight, until the satire is traded for sentimentality. Efforts to make the show moving are valiant if misguided. But the biggest problem is with our heroine, Elena. To be clear, Alyssa Martyn is great in the part, sounding super, smiling and simpering with the best of them. But this character, who would endanger Alison Bechdel’s health, is dead on arrival and doesn’t get any better in the afterlife.

So, we are left with the story of the Count and, thankfully, that’s an interesting one. Eccentrics can get away with a lot… although maybe not making life-size dolls of dead women. And it’s a great move to make sure Carl never realises how strange he is. Far too much rests on the lead, but the production is blessed with the casting of Wade McCollum. In fine voice, with excellent comic skills, he manages to make you feel for this wannabe Frankenstein, despite everything. McCollum has terrific stage presence and effortlessly propels us over the show’s flaws. Come for the crazy, stay for the star.

Until 18 August 2018

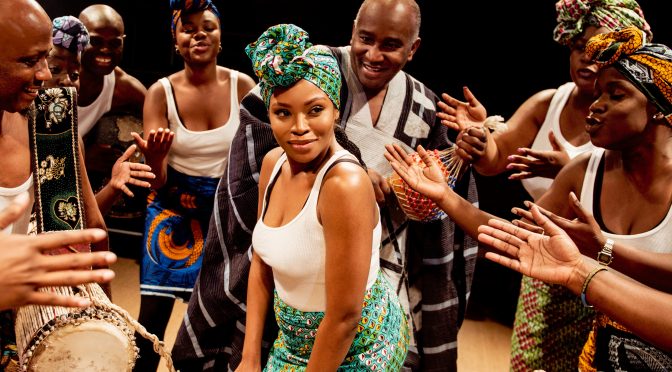

Photo by Darren Bell