Just before the interval during Jim Cartwright’s play, two young

unemployed characters, who have taken to their bed depressed, rage about their lives and imagine “the last job in the world”. It’s a startlingly contemporary moment, given speculation about the perilous future of employment, in a production too-happily rooted in the mid 80s of the play’s origin. The soundtrack, dialect, and accurate costumes in Chloe Lamford’s design, all serve to examine The North in Thatcher’s Britain, and they do so authentically. But, when combined with John Tiffany’s precise direction, a painful history is presented with a coldly anthropological air.

Life on an average road is presented in a series of short scenes, visiting different characters. There are frustrations with this snapshot treatment, but the standard of each scene is high and the anger from Cartwright and his characters stands in contrast to the clinical approach that prevails in this revival. Several monologues are highlights, in particular those with a nostalgic air performed superbly by June Watson and Mark Hadfield. The challenges of the text are meat and drink to the talented cast, who Tiffany has clearly worked closely with, nearly all of whom perform more than one role and differentiate characters superbly – none more so than Michelle Farley whose transformations astonish.

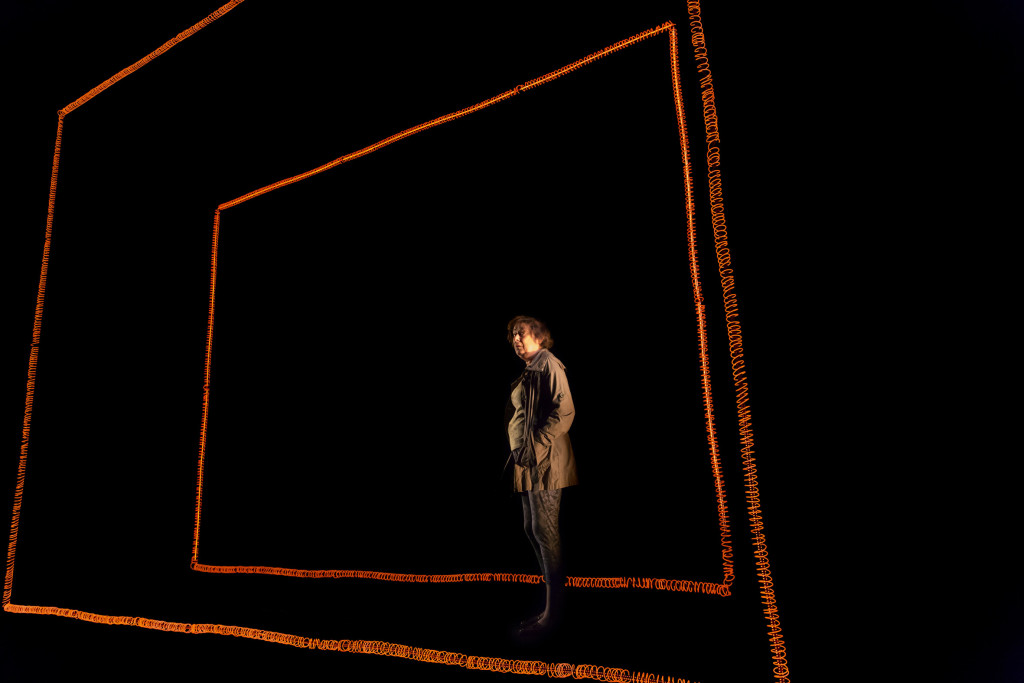

Our visit is guided by a narrator, played by Lemn Sissay. His

character’s focus is a good night out and jokes about the escapism of sex and alcohol threaten to take over, driven by Tiffany’s high energy approach. It’s left to Jonathan Watkins’ direction of movement to add gravitas and appreciate Cartwright’s poetry. That the show plays a little uncomfortably amongst the wealth of Sloane Square is testament to its confrontational approach. Cartwright appreciates the sharp wit of his protagonists – there are some very funny retorts here – but the laughs around the poor and uneducated come with a warning. Moods change within seconds, on the whim of a fraught nerve, and darkness prevails despite the production’s over-enthusiastic moments.

Until 9 September 2017

Photo by Johan Persson