This welcome return of Kneehigh’s much admired reworking of John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera is ripe for our times. The show is dark – recreating 18th-century villains in a world of corrupt politicians and organised crime, it pushes into pitch black territory. Politically crude and frequently rude, this is a protest piece with anarchic urgency that condemns money, power and the state of the world.

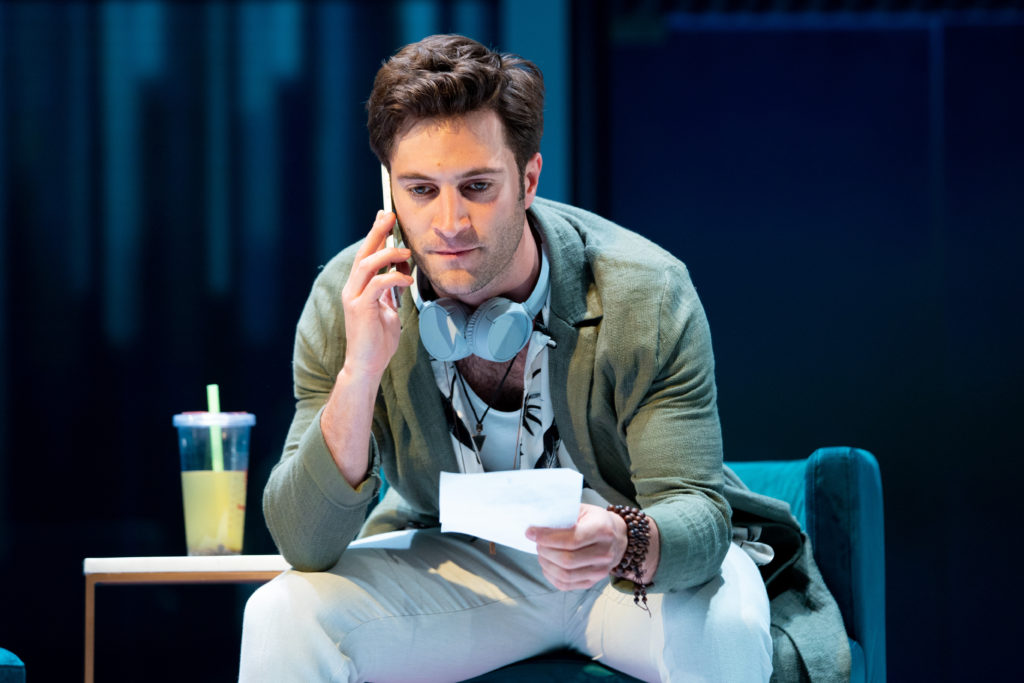

Writer Carl Grose is stark in his views of human nature, which is the key to the show’s satirical punch. The action is led by Martin Hyder and Rina Fatania, who give brilliantly overblown performances as small town mafiosos murdering their way to a mayoralty. For law and order, Giles King’s maniacal chief of police is frightening stuff, flip-flopping between bribery and blood lust. His target is Macheath, a sinister hitman in this version. Rendered cold rather than charismatic in Dominic Marsh’s sterling performance, Macheath brings the personal into politics, deciding between a life of love, a noble death or a career in crime. The result isn’t pretty. Interestingly, the sexual politics in the piece haven’t been updated as much as you might expect. Macheath’s women are still dopey for him, though the roles are performed with spice by Beverly Rudd and Angela Hardie.

Maybe the madness for Macheath is appropriate in a show that calls for a touch of chaos all around. Consider the music. All those songs promised in the title are eclectic to an extreme, and composer Charles Hazlewood’s range of references is awe inspiring. There’s a trade off with coherence – and few will enjoy all the numbers – but each song adds to the crazy appeal of the show, and the energy from Mike Shepherd’s direction, with his talented cast of actor musicians, is considerable. The detail throughout is fantastic, not just with Grose’s tongue-tying script – this is a keep-your-eyes-peeled show. With swapping suitcases and plenty of multiple roles (Georgia Frost does especially well here), you don’t want to miss a moment.

While the call for changes in society and for personal responsibility are not convincing enough in this grim vision of our state, they are depicted well through the only character we come close to caring for – Patrycja Kujawska’s Widow Goodman forms the spine of the show (and her violin playing is fantastic). It’s a shame that Punch – yes, as in Judy – gets the last word. While Sarah Wright, who led the puppetry on press night, is fantastic, Punch’s nightmarish commentary ends up overwhelming. That Punch talks most of the sense on stage is downright depressing. We’re not in that much trouble, are we?

Until 15 June and then touring until 13 July 2019

Photos by Steve Tanner