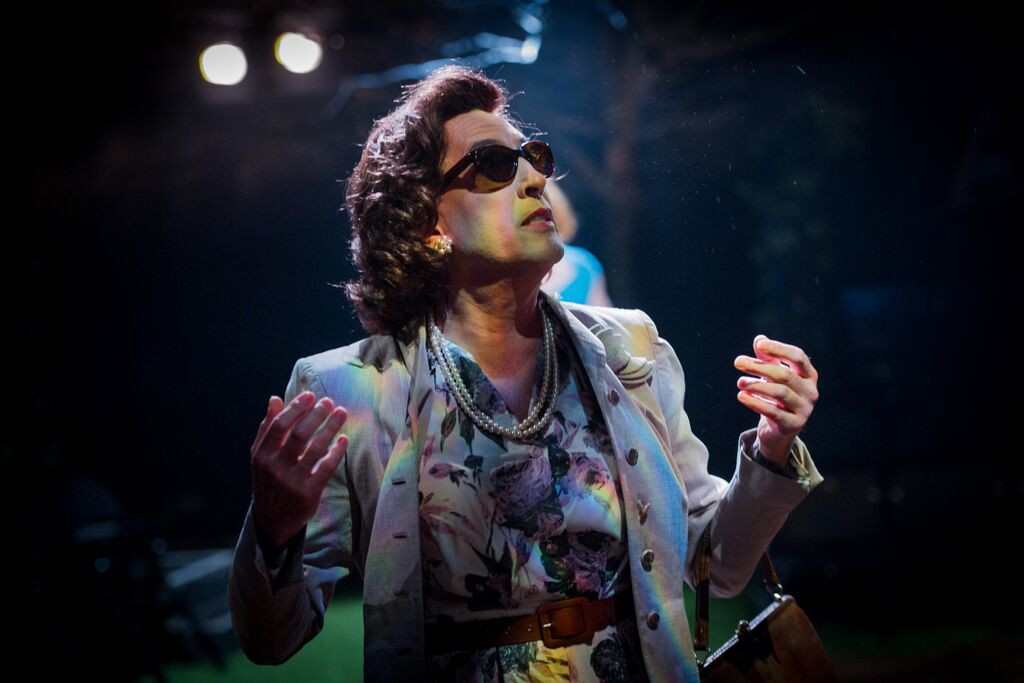

This play should come with a health warning: following the journey of a drink and drug addict is never going to be easy viewing. Headlong’s new co-production at the Dorfman Theatre is hard work, but it is testament to Duncan Macmillan’s script and an astonishing performance by Denise Gough that the play can be described as unmissable. Gough should clear the mantelpiece for awards – standing ovations are rare at the National Theatre and I can’t remember joining one at a matinee performance.

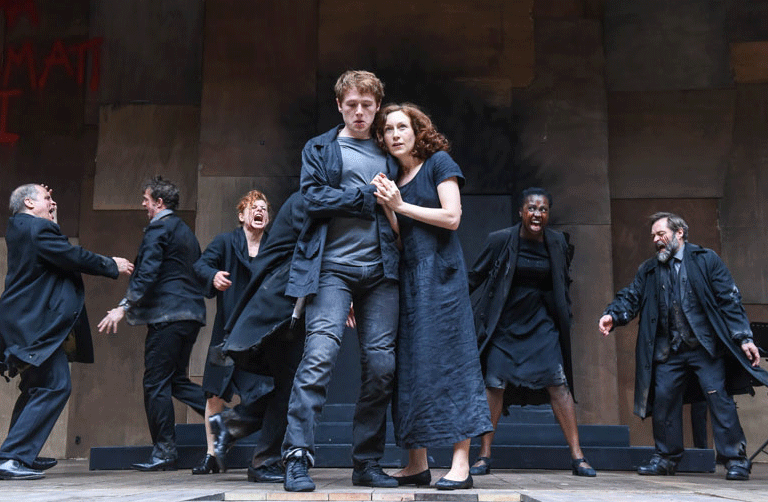

Playing Emma is a punishing lead role and Gough delivers a raw performance that engenders anger, frustration and occasionally repulses. To add to the trauma, Emma is an actress and Macmillan uses performance, indeed the process of staging a play, as a parallel to her counselling sessions. As Emma joins a group, sitting in a circle, introductions are made, just like at the start of rehearsals, and then role-play undertaken. It feels dangerously close to the bone.

Playing Emma is a punishing lead role and Gough delivers a raw performance that engenders anger, frustration and occasionally repulses. To add to the trauma, Emma is an actress and Macmillan uses performance, indeed the process of staging a play, as a parallel to her counselling sessions. As Emma joins a group, sitting in a circle, introductions are made, just like at the start of rehearsals, and then role-play undertaken. It feels dangerously close to the bone.

Particulars of the addicts’ stories are brief – Emma’s is obfuscated by compulsive lying – so we don’t get to the bottom of why they are in such trouble. It’s not misery that’s dissected here but recovery, with tension and a healthy amount of scepticism. No one has more reservations about her 12-step treatment than our articulate protagonist. But burning through an agenda of denial, which serves to intelligently explore AA, comes the simple desire to survive.

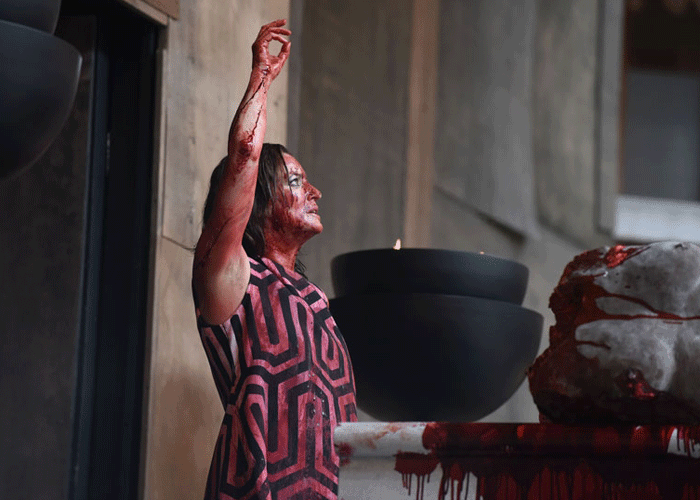

Carefully directed by Jeremy Herrin, the staging is particularly effective when it comes to Emma’s hallucinations, which are downright spooky. Overall, Bunny Christie’s set feels too flashy and polished – the play simply doesn’t need it. And though there are jokes and nervous laughter from the audience, I confess my sense of humour deserted me, as what was going on was overwhelmingly bleak and serious.

Macmillan doesn’t hold back; the selfishness of the addict is emphatically depicted. A final scene with Emma’s parents is particularly painful (Barbara Marten gets to play her third role of the show and is excellent in each) after observing what Emma has been through. Here’s the second side to that health warning: I don’t know if Macmillan had a didactic motivation, but I feel I learned a lot about what an addict must go through, and feel humbled as a result.

Until 4 November 2015

Photo by Johan Persson