While Githa Sowerby’s 1912 play has long been acknowledged as an important text, Polly Findlay’s new production reveals the work to be a true masterpiece. No doubt old-fashioned, being driven by a strong plot featuring excellent characters and dripping with detail, the piece contains bigger concerns that feel remarkably contemporary. The story of a tyrannical patriarch who lives for his factory at the expense of his family, the obsession with legacy and reputation may be removed from our times, but Rutherford’s business model is easily recognisable.

At the centre of the play is Rutherford himself – a mammoth role that Roger Allam takes in his stride. Allam is so good he can allow humour into the part, which is important as the sexism, snobbery and bullying are hard to swallow. And, for all the awful things Rutherford says and does, Allam manages to inject a compelling charm. It’s easy to imagine his workforce and family being devoted to him. Rutherford’s character is revealed slowly – notably he is talked about a great deal before we meet him, which gives us a complex person rather than a caricature. Given his cultivated pretence of reasonableness, you may find yourself agreeing with him more than you’d like, even when he’s at his most outrageous.

Allum is amazing, but it’s Findlay’s triumph that, unlike Rutherford, he isn’t totally in charge. A superb supporting cast moulds the focus of the play from scene to scene. Harry Hepple and Sam Troughton play the hapless sons, a mix of timid piety and privileged bluster that’s increasingly unattractive. There’s a brilliant performance from Justine Mitchell as the daughter, Janet, who provides evidence of the cruelty brought to all the siblings’ upbringings. The outcome of her story, containing a shock and a mystery, is deeply moving. It’s in his daughter-in-law, Anjana Vasan’s Ann, quiet for so much of the play, that Rutherford meets his match, with a finale that makes ruthless bargaining a riveting drama.

Rutherford and Son could so easily be dismissed as all about repression – hence less relevant to our times. But there’s actually plenty of confrontation in the play and presenting both shows Sowerby’s genius. The characters aren’t pushovers – they wouldn’t convince if they were. Rather, quiet moments, in particular the depressing resignation the women often display, create a distinct rhythm for the piece that builds in power. Although bleak, there’s a sense of satisfaction that Rutherford is justly rewarded. Given that he’s a glass manufacturer, a profession Lizzie Clachan’s gorgeous set emphasises, the danger of throwing stones should be clear. Or maybe that’s wish fulfilment on my part? The finale has a Rutherford heir who isn’t quite the son anyone presumed. Questioning what might come next is Sowerby’s aim, highlighting motherhood makes this a play focuses on the future far more than for the past.

Until 3 August 2019

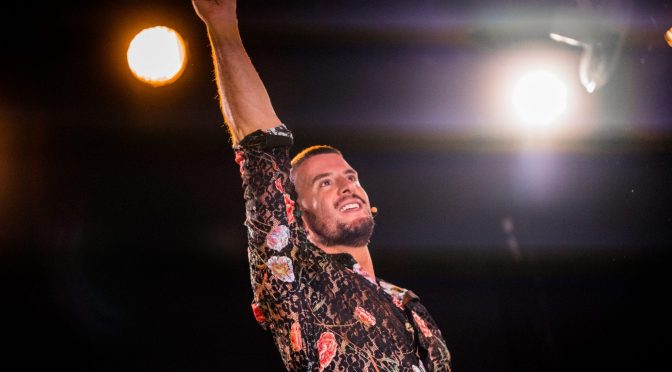

Photos by Johan Persson