Marianne Elliott’s new production of Stephen Sondheim’s musical gained great press when it was announced that the gender of the lead would be swapped. Bobby, the still-single thirty-something, pressured and puzzled by commitment, becomes Bobbie. The change adds an urgency to debates about marriage that the show explores, adding the pressure some women feel to have children. But the joyous surprise is how remarkably easy the alteration feels. If you didn’t know the piece you wouldn’t guess at any fuss. A frequent argument in theatre is resolved conclusively. And that’s just the start of this show’s many virtues.

Rosalie Craig is in the spotlight and she is brilliant. Even though she’s barely off the stage, and everyone is talking about her character, Bobbie has to take a back seat as her friends’ marriages are examined through fantastic songs. Craig achieves this with, well, grace – I can’t think of a better word. Throughout the show, and even when it comes to her big numbers, Craig brings a coolness to the role that ensures her character’s questioning is communicated. Frequently looking to the audience, exclaiming ‘Wow’ more than once, she shares the oddities she sees with us. It’s a perfect reflection of Sondheim exploring friendship and love with complexity and openness.

It’s another achievement on Elliott’s part that a star as big as LuPone fits the show so well. There’s a Broadway feel to the production that’s appropriate to the story’s location, but which surely has an eye on a transfer – it deserves one. If there’s a tiny cavil, the pace occasionally feels driven by a desire to display value for money – even if every minute is enjoyable, a couple ofscenes are drawn out. But Company is as close to flawless as anyone should care about. Bunny Christie’s design is stunning– this is a set that actually gets laughs. Rooms, outlined in neon, connect characters in the manner of a farce, while playing with scale gets more giggles. Elliott employs an Alice InWonderland motif that is no laughing matter.

With the couples watched, there isn’t a poor performance. Mel Geidroyc and Gavin Spokes are great fun as the squabbling Sarah and Harry – will karate help their relationship? While Jonathan Bailey gives a show-stopping turn as Jamie, in a panic on his wedding day. Previously Amy, his relationship with Paul (played by Alex Gaumond) is a delicious modernisation. But the biggest casting coup? The legendary Patti LuPone takes the part of the acerbic Joanne and is simply unmissable. Every line from LuPone lands. Every gesture captures the audience. And her rendition of TheLadies Who Lunch is revelatory – to make a song like that your own takes real class.

It’s another achievement on Elliott’spart that a star as big as LuPone fits the show so well. There’s a Broadway feel to the production that’s appropriate to the story’s location, but which surely has an eye on a transfer – it deserves one. If there’s a tiny cavil, the pace occasionally feels driven by a desire to display value for money – even if every minute is enjoyable, a couple ofscenes are drawn out. But Company is as close to flawless as anyone should care about. Bunny Christie’s design is stunning– this is a set that actually gets laughs. Rooms, outlined in neon, connect characters in the manner of a farce, while playing with scale gets more giggles. Elliott employs an Alice InWonderland motif that is no laughing matter.

It isn’t just Bobbie’s gender that has changed – she is now a Millennial. There’s no crude casting as a snowflake, but one wonders if she might be infantilised? There are party games at her 35th birthday, after all. Elliott makes a point about life – now – that is subtle and topical. Credit to Sondheim’s piece, of course, so full of themes ripe for development. But it is the production that makes it hard to believe the piece is nearly 50 years old – Bobbie and her crowd always feel contemporary. For all the joys of the show, it is seeing a director use a piece with such skill and invention that makes this Elliott’s triumph.

Until 30 March 2019

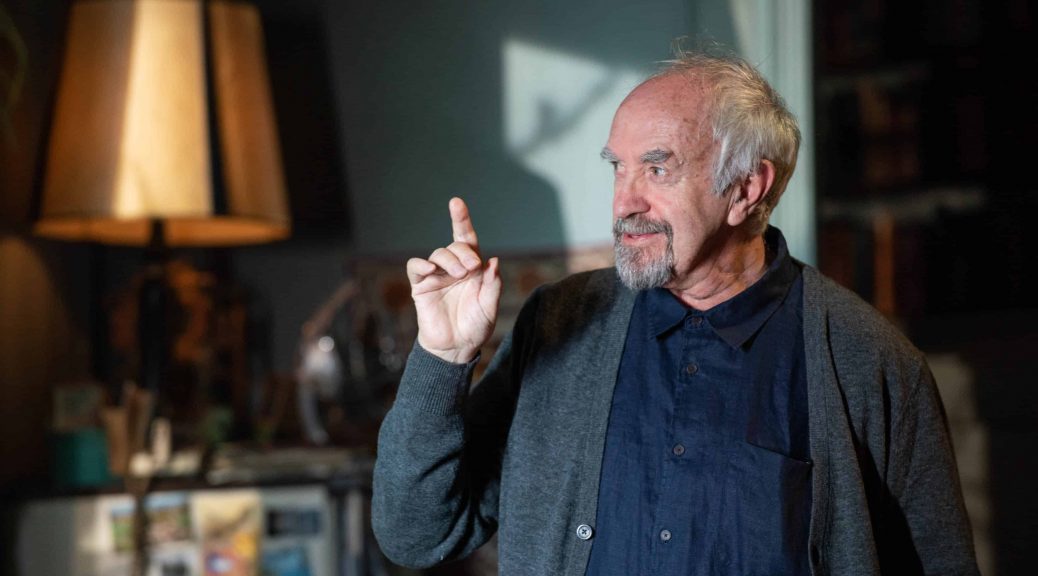

Photos by Brinkhoff Mogenburg