A play that comes with its own stars, albeit an excessively modest two of them, Stephen Adly Guirgis’ Broadway hit may have a title that fits uncomfortably with the National Theatre’s augustness, but The Motherf**cker In The Hat is a quality play that London should welcome. Detailing the struggles and affairs between a drug addict on probation, his ‘sponsor’ and their girlfriends, the work’s vigorous language belies its old-fashioned enquiry into morality.

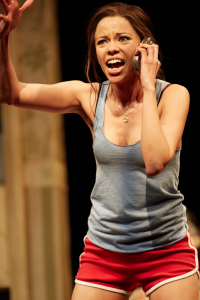

Ricardo Chavira plays Jackie, a troubled convict following a plan to free himself from addiction with a suitably cynical edge, making our hero hugely appealing despite his faults. Flor De Liz Perez (pictured) performs as Jackie’s partner, delivering vicious tirades with verve. Also from the States comes Yul Vázquez as Cousin Julio, delivering a marvellously understated, original performance. Completing this strong cast, directed flawlessly by Indhu Rubasingham, are Nathalie Armin as the unfortunate wife of the rehabilitated Ralph, the philandering sponsor with a PhD in persuasion, depicted brilliantly by Alec Newman as a devil who firmly believes he has all the best lines.

Ricardo Chavira plays Jackie, a troubled convict following a plan to free himself from addiction with a suitably cynical edge, making our hero hugely appealing despite his faults. Flor De Liz Perez (pictured) performs as Jackie’s partner, delivering vicious tirades with verve. Also from the States comes Yul Vázquez as Cousin Julio, delivering a marvellously understated, original performance. Completing this strong cast, directed flawlessly by Indhu Rubasingham, are Nathalie Armin as the unfortunate wife of the rehabilitated Ralph, the philandering sponsor with a PhD in persuasion, depicted brilliantly by Alec Newman as a devil who firmly believes he has all the best lines.

It can’t be denied that the play is reminiscent of a soap opera (or should that be a telenovela?), but the sordid plot twists, while predictable, are expertly handled and feel believable. Likewise, the bad language and lurid insults play their part, not just in making the script very funny, but in creating characters you really fall for. For all the shouting on stage, this is a work that quietly ensures we take seriously the questions it’s asking – about how to be good.

The play is calmer, less surreal, than Adly Guirgis’ other works seen in London. It’s tempting to say it feels more grown up, as that’s clearly one of the themes here; the talk of prayers and pharmaceuticals both play a part in questioning responsibility and relationships. Jackie and Ralph are just young men, with more than enough faults and few excuses. But Jackie has a heart and the potential for goodness that feels realistic and makes this play an unusually sharp comedy.

Until 20 August 2015

Photo by Mark Douet