First performed at the Royal Court in 1958, Arnold Wesker’s Chicken Soup with Barley is the story of Sarah Kahn, a dedicated East End communist, and her struggle against capitalism. Director Dominic Cooke’s revival of this state-of-the-nation period piece does justice to Wesker’s ability to unite the political with the personal.

The play opens on the day of the Battle of Cable Street, on 4 October 1936, and the characters’ enthusiasm for rioting seems strangely quaint. When Sarah reaches for the rolling pin it gets a laugh and handing a Communist flag to her husband, telling him to “do something useful,” takes on a delicious irony.

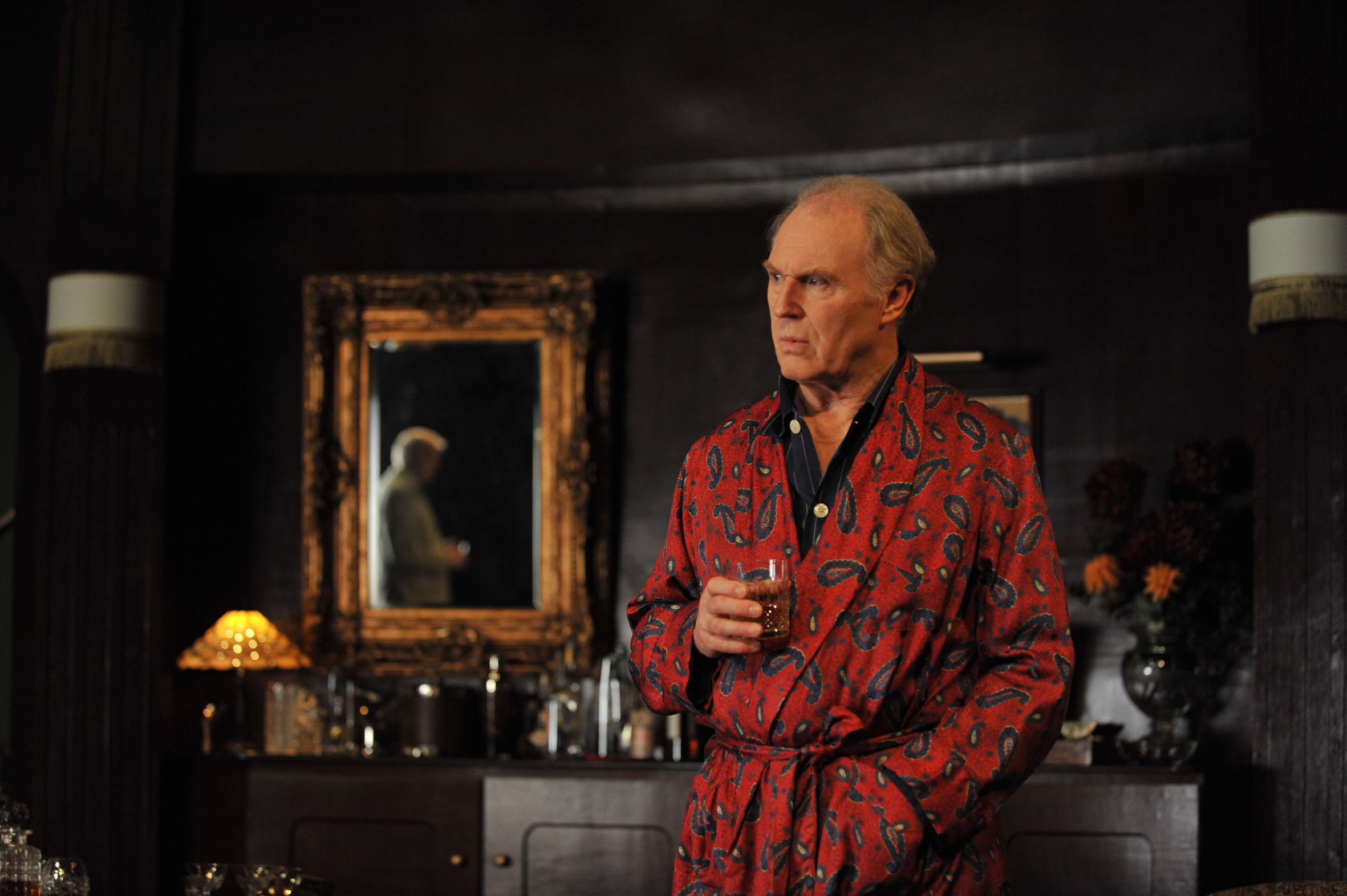

Chicken Soup with Barley is a convincing family drama. Sarah’s husband Harry’s lack of political involvement is only the start of their marital problems. In these roles, Samantha Spiro and Danny Webb give tremendous performances. As the story spans three decades, the actors have plenty of opportunity to show off their technical prowess (Spiro has done this before – she seems capable of playing any age). But what really impresses is the close emotional bond one can sense, despite their cruelty to one another.

The arguments between the couple, including the fight for a socialist future, take their toll on their children. Here are two fine professional debuts, with Jenna Augen as Ada establishing her character’s complexity with impressive speed, and Tom Rosenthal as Ronnie providing a moving and astute performance.

Hindsight might make rebellion against their mother’s ideas seem predictable, but it is Cooke’s masterstroke to open up this division and make it so emotional. In a production that often feels rushed, time is taken to remind us of Ada’s absence, while Ronnie’s rejection of the ‘Party’ has apathy at its core. And that makes the themes in Chicken Soup with Barley seem relevant today. Londoners still protest, but our riots are reactionary not revolutionary. Fortunately for Cooke, the heart of Wesker’s political comment is engagement and a repeated desire to debate and act that becomes not just compelling drama but an important message that is clear and loud.

Until 16 July 2011

Photo by Johan Persson

Written 13 June 2011 for The London Magazine