Verbatim theatre, with the script transcribed from everyday speech, is relatively rare. As for a verbatim musical – I can only thing of Alecky Blythe’s hit London Road. So doubling the genre, with music by Tom Derring, this new show counts as a curiosity, while suggesting the novel treatment has potential.

The subject matter might make you question the sanity of the project. The piece’s full title is The Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee takes oral evidence on Whitehall’s relationship with Kids Company. Yes, it’s a crazy idea. But it works well.

For further originality, the book and adaptation into lyrics, by Hadley Fraser and Josie Rourke, use not the casual conversations admired in most verbatim works, but public testimony in the House of Commons – speech that contributors knew would be on record.

Topical, political, important – all fine qualities for good theatre. It’s clear that, despite the humour, including initial giggles at people bursting into song, this is serious stuff. The cast excels at depicting the MPs we came to know during the news story – Alexander Hanson and Liz Robertson are especially strong as Bernard Jenkin and Cheryl Gillan – but coming so close to impersonations can be distracting. Thankfully, the show isn’t flattering about anybody’s sense of importance – or their desire to capture the “8.10 slot” on the Today programme.

Being grilled are none other than Alan Yentob and Camilla Batmanghelidjh, the Kids Company charity’s trustee and CEO. The roles are taken by opera singer Oscar Ebrahim and, with a voice to match him, Sandra Marvin. Again, while their impersonations are eye catching, the real achievement is a vocal ability that aids in revealing the complexity of characters and the situation. They add weight to Deering’s compositions and, while the show is static, some clever touches from director Adam Penfold are well used.

While you might find yourself surprised at how entertaining the whole thing is, Committee’s biggest success is drier – it works as a peculiar pedagogy. The MPs sing that their aim is not a show trial but “to learn” what happened to the bankrupt charity. And from this condensed 80 minutes you discover the issues and questions far more efficiently that following the story in the media. The edit deserves credit, of course, but the ability of the music to focus the mind has a strange power I’d happily hear utilised more often.

Until 12 August 2017

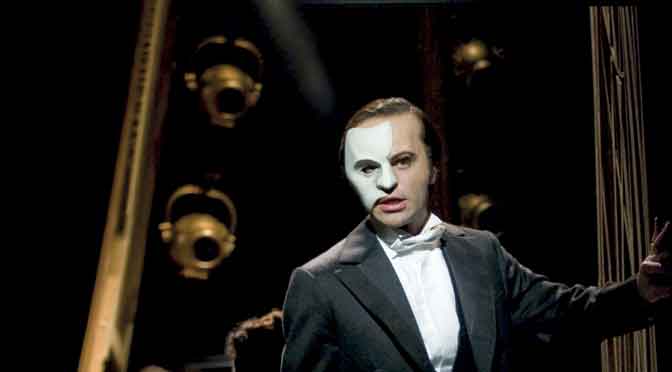

Photo by Manuel Harlan