Having just celebrated its first anniversary, a spectacular year that has seen this new theatre run by Lucy Bailey and Anda Winters establish itself as an essential fringe venue, The Print Room presents Judgement Day. The play is a new version of Ibsen’s last work When We Dead Awaken that the adaptor Mike Poulton describes as Ibsen’s ‘confession’ about the price paid for a life lived for art.

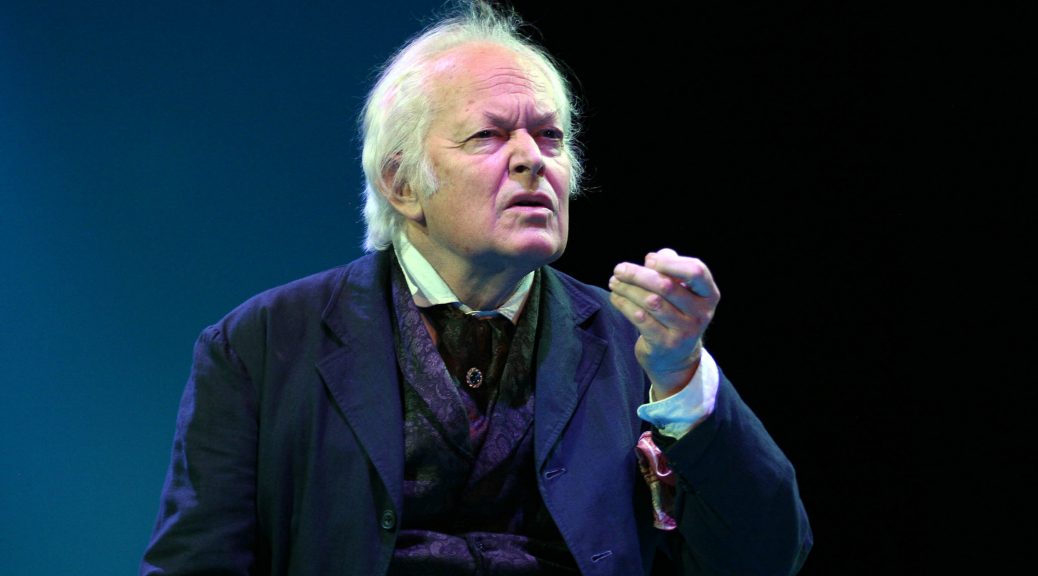

Arnold Rubek, a renowned sculptor, is the kind of Romantic artist who’s hard to like and easy to mock. Quick to proclaim his genius and espouse aesthetics, he is aware that he has ‘sold out’. In a loveless marriage and on a constant holiday, he re-encounters his first muse, Irena – an ‘association’ neither of them has ever recovered from. Michael Pennington is engrossing as the objectionable Rubek, taking us past the character’s pomposity to make him profound.

Poulton’s version makes Ibsen’s concerns seem fresh and he brings out the master’s lighter touch when it comes to the women who have suffered from being in Rubek’s life. Sara Vickers plays Rubek’s much younger wife, Maia, brimming with intelligence and frustrated sexuality. She is so bored that when a dashing baron arrives on the scene, she’s willing to accept a trip to see his dogs being fed as a first date. Where Maia is full of life, Irena, Rubek’s old muse, lives in the past. Penny Downie convinces in this hugely difficult role, toying with her character’s ambiguity and succeeding in being always believable. No easy task when you’re being followed around by a nun as your rather Gothic fashion accessory.

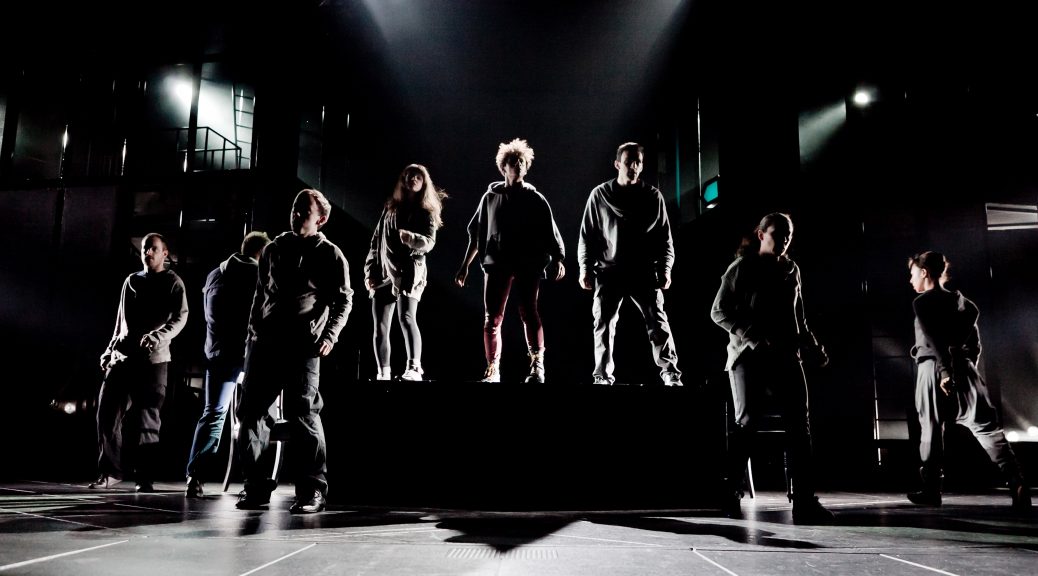

Judgement Day is heavy on symbolism but Poulton’s text and James Dacre’s direction also deliver a gripping human drama. The language is poetically satisfying and accessible, giving you plenty to ponder on at the end of the play’s 80-minute run. The Print Room has a hit on its hands and, while you are buying your ticket, take my advice and book up for its next production, Uncle Vanya, at the same time.

Until 17 December 2011

Photo by Sheila Burnett

Written 22 November for The London Magazine