Teunkie Van Der Sluijs’ idea of adapting Theo van Gogh’s 2003 film for the stage isn’t a bad one. Taking us behind the scenes of a celebrity interview has the scope for a tight head-to-head piece. Regrettably, the potential isn’t realised here. Updating the scenario to include the internet is poorly handled – it isn’t clear when the play is actually set – and the show ends up a long 90 minutes that tells us little.

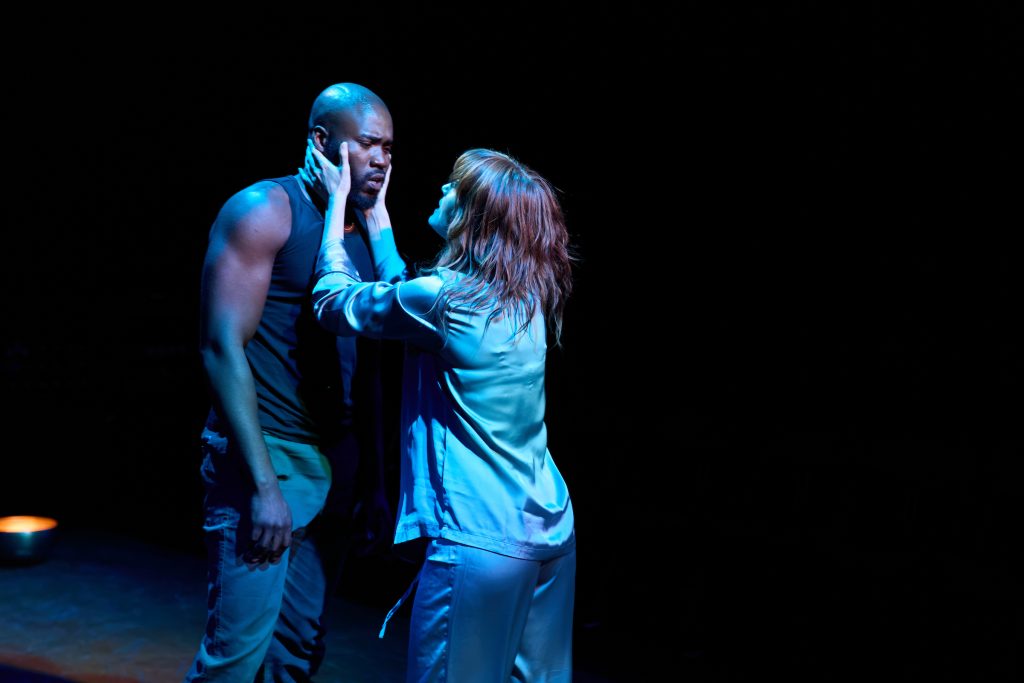

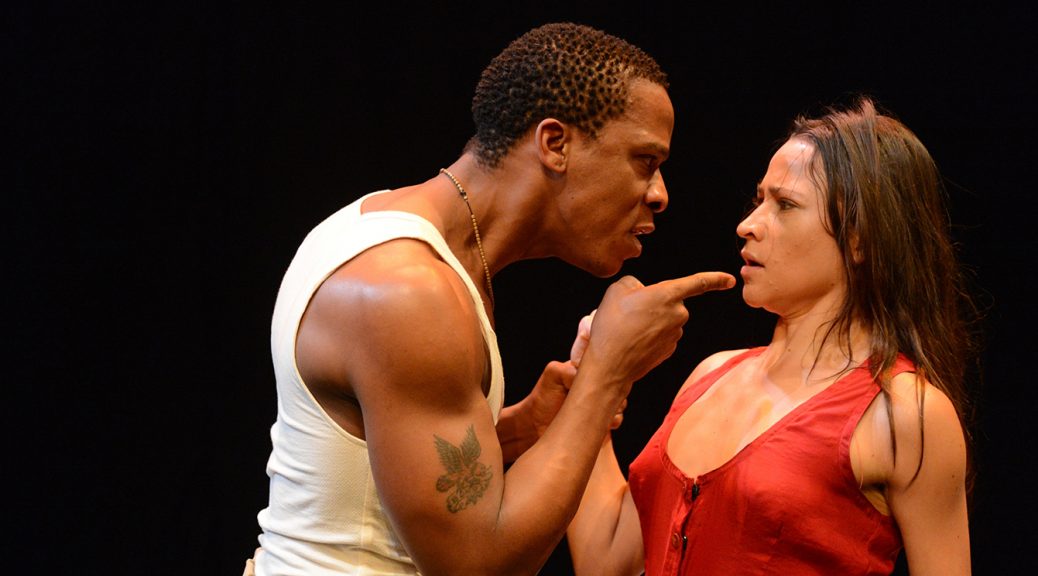

The tension between serious journalist Pierre and influencer-turned-actor Katya just isn’t as strong or as interesting as it needs to be. The performers, Robert Sean Leonard and Paten Hughes, work hard. While Pierre seems ridiculously naïve, he has a traumatic back story that Leonard does well with. Poor Hughes has a tougher job, as her character’s intelligence and duplicity are supposed to, somehow, surprise us. But apart from this, there really isn’t enough to separate these two self-obsessed compulsive liars to create any sense of conflict.

Van Der Sluijs’ direction gives too much time to what little action there is and the players are somewhat swamped by the lavish Brooklyn apartment set. But there are no complaints about the production, which looks and sounds good, with an atmospheric score from Ata Güner. The video work, including live recording, is also good and incorporated very well. But – and it’s nobody’s fault here – there’s just too much of this sort of thing around right now.

Problems continue with the script’s poor humour and the odd chemistry between the characters. Some of this might interest – there are some fine #MeToo moments – but the observations and the jokes, like the opinions and a lot of the plot, are exactly what we’d expect and they feel dated. The whole idea of Katya turning the tables – and a poor final twist – are predictable. Some of this is deliberate, playing on expectations, but does an audience in 2025 really think that a social media star is stupid? Or that a journalist has integrity?

Interview wants to say lot to say about truth – online, in the news, surrounding celebrity – and how this triad relates. You might side with Pierre or see Katya’s POV. Maybe who you prefer depends on who you deem to be less irrelevant. But I’m afraid you won’t hear anything that you haven’t heard before and there’s little challenge or excitement. Maybe that’s a reflection on our times. But all we have here is battle of wits between two narcissists, neither of whom are as clever as they think they are.

Until 27 September 2025

Photos by Helen Murray