With a trio of companies behind it – and, don’t forget, links for donations – the National Theatre, Fuel and Leeds Playhouse gave us something for the weekend with Inua Ellams’ play. This recording, from the London run in 2018, reminds us why this piece – which covers vast ground geographically and brings up plenty for debate – was so warmly received.

Scenes in barber shops in London, Lagos, Accra, Kampala, Johannesburg and Harare add up to a lot. And we encounter plenty of colourful characters (Patrice Naiambana’s Paul was my favourite although Hammed Animashuan’s performance was brilliantly scene stealing). Alongside a powerful drama between Emmanuel and Samuel, which make good roles for Fisayo Akinade and Cyril Nri, there are all manners of observation on language, politics, race and culture. It’s all interesting, although maybe not always subtle, but it could easily be overwhelming.

Ultimately, these chronicles are a collection of small studies and intimate scenes. Director Bijan Sheibani skilfully combines the big picture with close details, and the result belies any shortcomings. Ellams’ touch is light, while segues between scenes, with singing and dancing, are excellent. What could be confusing proves energetic. And the play is funny: jokes are used pointedly and there’s plenty of wit to enjoy.

While the barber shops, as a “place for talking”, serve as an effective device for holding the play together, what really does this job is the theme of fatherhood. The stories take in violence and various ideas of legacy and inheritance, offering plenty of insight. And it’s interesting to note how much bigger than biology the theme of parenthood becomes. Connections between the characters are handled carefully (until the end, in a clumsy moment that really disappoints). Ellams’ play, with Sheibani’s help, ends up more than the sum of its parts. And, given that it has more parts than a barber shop quartet, that’s really saying something.

Available until Wednesday 20 May 2020

To support visit nationaltheatre.org.uk, fueltheatre.com, leedsplayhouse.org.uk

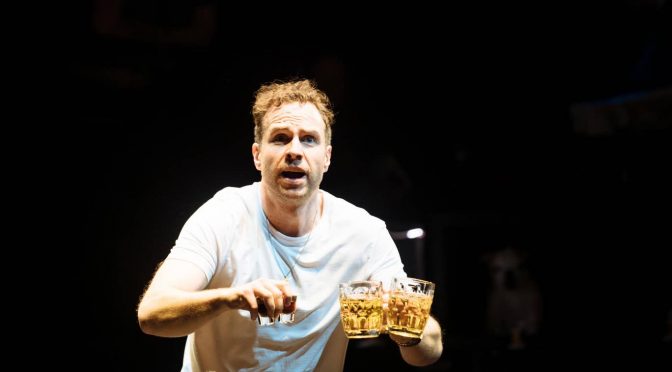

Photos by Marc Brenner