Humour and sentiment can be an uncomfortable mix. The secret of Tim Firth’s successful career, from Neville’s Island to the recent Calendar Girls, is that he combines them so well. Sign of the Times shows off this talent on an intimate scale – its heartwarming stuff with plenty of laughs.

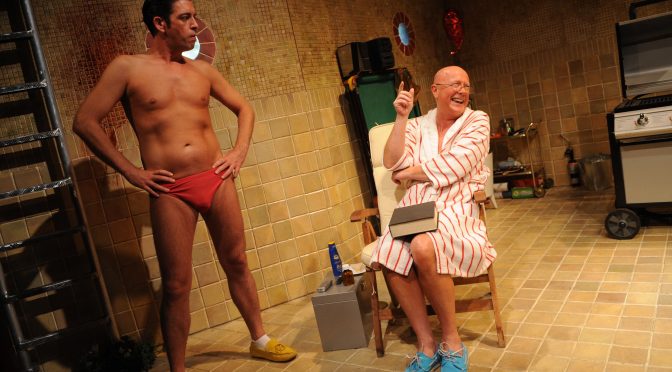

Matthew Kelly plays Frank, Director of Installations at a sign manufacturer who is given the added responsibility of looking after Alan (Gerard Kearn) who is on work experience. Like many an intern, Alan is getting a raw deal here – he wanted work experience on the set of Emmerdale but instead is stuck on top of an office roof with a bore.

This is a comedy about a generation gap with the age-old twist of who is actually learning most from whom. Young Alan’s creativity strikes a chord with the older man, who is a frustrated writer. No matter how bad the spy thrillers he dictates during breaks are, we are touched by the sincerity of his efforts – he has a “burning burn” to write and who can argue with that! And the inspiration to do more with his life comes at the perfect time – the sign they are currently erecting spells out the end of his career.

Three years later, the roles are reversed. Alan is now the eager Trainee Assistant Deputy Manager explaining Frank’s new job to him with corporate mnemonics ripe for satire. It’s Frank’s turn to inspire and remind the youth of the courage he once had, saving him from electrocution along the way.

Sign of the Times started as a one-act play and there are moments when Firth’s extension seems contrived. Frank’s story reminds us that postponing retirement age entails problems, but that isn’t where the strength of the story really lies.

Firth writes great characters and in Sign of the Times they get the performances they deserve. Kelly is fully in control of the stage, charming even when pompous and endearing in his enthusiasm, and Kearns (who may be recognised from Shameless) makes a great West End debut. Both actors are spot on with their comic timing and make Sign of the Times well worth seeing.

Until 28 May 2011

Photo by Simon Annand

Written 14 March 2011 for The London Magazine