Lewis Aaron Wood’s well-intentioned play is elevated by the work of director Daniel Blake. If this examination of the mental health problems of a rugby player – Ed – is not as insightful as might be hoped, Blake’s staging is strong, and his cast’s performances are impressive.

Aaron Wood has focus, and Bones is neatly written. While the dialogue is occasionally stilted, this reflects the play’s characters, who are believable, if not compelling. Ed says surprisingly little about his depression and anxiety, or even his recently dead mother. Of course, reticence is part of the point. But interactions with family and friends show his problems are a poorly kept secret, so tension in the piece doesn’t work dramatically.

Ed cannot manage an “injury that doesn’t heal”, and the connection between physical and mental health, highlighted through sport, shouldn’t be a revelation to anyone. Moreover, the machismo of the rugby team is well-trodden ground. Instead, it is when Aaron Wood writes about the game itself that the script takes off. Presenting rugby as a “safe space” is a smart irony.

While the play is better on sport than on mental health, there are plenty of secure performances to be proud of, especially in Ronan Cullen, who takes the lead and complements the script. Cullen does not stress his character’s pain – Ed wouldn’t do that – but he brings an intensity to the role that is commanding. Ed’s friends make strong roles for Ainsley Fannen and Samuel Hoult. Fannen brings out some laddish humour well (another strong point of the script), while showing us a silly but sensitive young man. Hoult’s character also convinces, but it’s a shame the dynamic of his being slightly older isn’t explored more. Last but by no means least is the hardworking James Mackay, who takes on multiple roles including Ed’s father, another character who could easily be developed.

The talented cast excels when it comes to Blake’s ambitious direction of scenes on the rugby pitch. The physicality is hugely impressive, with everyone throwing, catching, forming scrums and tackling one another. These scenes, enhanced by Eliza Willmott’s sound design, are hugely effective and almost frightening in such a small theatre! While this is an uneven show, the games and training are brilliantly depicted and match Aaron Wood’s most inspired moments.

Until 22 July 2023

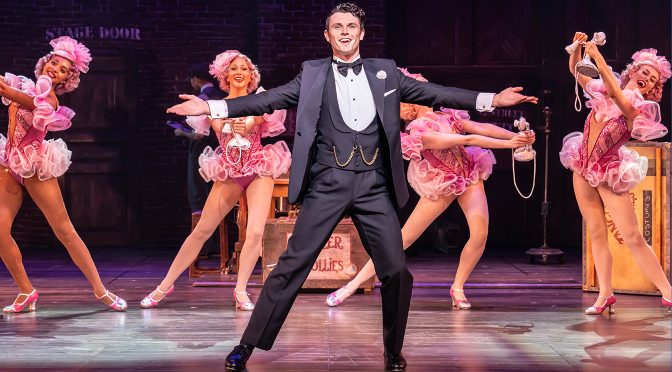

Photo by Charles Flint