Schaubühne Berlin director Thomas Ostermeier’s production invigorates Ibsen’s classic. With the characters made so clearly contemporary, the story of personal morals and political hypocrisy feels fresh. A star cast responds to the energy, making the show, co-adapted with Florian Borchmeyer, bracing.

Doctor Stockmann (Matt Smith) and his friends are “hokey cookie liberals”. They are in a band, drink wine from tumblers and wear normcore. We can guess what paper they read. There’s a gentle sense of cynicism around them that skilfully develops bite. For when Stockmann discovers poison in the town’s water system, his pretty cool life becomes a hot mess.

You’d think these nice folk would rise up against the “pink-faced geriatrics” of the establishment. Such enemies are embodied by the town mayor, who Paul Hilton makes suitably slimy. But things aren’t that simple. Stockmann’s old school friends Billing and Hovstad (played by Zachary Hart and Shubham Saraf) abandon their principles. And the mayor just happens to be the doctor’s big brother.

The family relationships in the show are explored well. Hilton makes such a good politician you almost start to believe his protests about trying to help. Nigel Lindsay gets a lot from the role of a father-in-law although how he ‘helps’ is too rushed. And there’s Stockmann’s long-suffering wife, Katharina, given a strong sense of autonomy in Jessica Brown Findlay’s excellent performance.

While Ostermeier makes a big effort to open the play up, it’s hard not to see it as Stockmann’s – and therefore Smith’s –show. The character and performer are magnetic. And it’s great to see the seeds of a mania so carefully sown. But Stockmann isn’t an appealing character, even if we admire him. Even his naivety – at one point he thinks people will be grateful to him for ruining the local economy – gets laughs rather than sympathy.

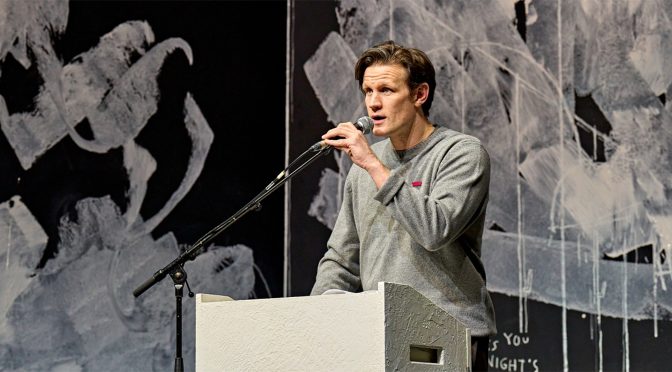

Stockmann is hurt by betrayal, but his main target is identified at a public meeting. There are bigger problems than left, right or centre – as a disturbing rant reveals. The idea that all opinions are valid, that we can ignore science or the truth, is attacked. It’s a memorable scene, with the house lights raised and an invite to get the audience’s opinion. The idea startles and is sure to make the production memorable.

Anyone joining in might do well to remember that it isn’t Stockmann who wants to know what we think – his mind is made up. The delivery is excellent, and Smith really comes into his own. So does Jan Pappelbaum’s black and white set, for that matter. I don’t want to knock Ostermeier’s anger. And we’re given room to question it all – Stockmann does come across unhinged and the outcome of the action is open. But there is a big flaw to all this. The piece wants arguments to excite, ideas to thrill. And while the execution is strong, I’m not sure either are strong or new enough to really do that.

Until 13 April 2024

Photos by Manuel Harlan