Let the cooking puns commence: Sarah Bareilles’ Broadway hit has arrived in London. An appetite for the show is easy to understand – it has charm and a great leading lady. The story is an everyday tale from a female perspective with surprisingly gritty touches: a welcome change for such a crowd-pleasing, mainstream project. It’s essentially a show about motherhood, which makes it hard to knock and easy to be moved by. Nonetheless, Waitress is not to all tastes.

Despite efforts at realism showing life’s sour side, the show is (sorry) too sweet. Its ‘Queen of Kindness’ heroine Jenna fails to convince, despite Katharine McPhee’s efforts. Meanwhile her salt-of-the-earth friends, played by Marisha Wallace and Laura Baldwin, who sound fantastic, are sketchy characters. All these lives revolve around men – at least, until Jenna has a baby – and you don’t have to be much of a feminist to think that’s not good enough for 2019. Still, the trio are heart-warming, the performances winning, and the book from Jessie Nelson has a nice grasp on an early midlife crisis, alongside an interesting take on American ideals. In short, it’s not devoid of ideas.

The songs are good from the start and get better throughout. There’s an excellent main refrain and a stand-out number. A strong country music feel, with a touch of the musical Once, the score is by far the best thing about the show. And the delivery is superb. McPhee is visiting from the States and has real star quality. How much she overshadows everything else is a tricky issue – Jenna is a massive role and, ultimately to the show’s detriment, all the other characters feel insignificant. The humour is terrible: adolescent nudges at sex, a sassy African-American and couple of geeks are very dated. Diane Paulus’ direction is efficient and brisk but cannot gloss over the bad jokes.

A selection of dire roles for men makes you wonder if a point is being made about the poor parts women have had to suffer in the past. And none of the men performing helps give any role depth. There’s the odious husband who takes Jenna’s cash and demands she love him more than her unborn child, and the gynaecologist she has an affair with (in his consulting room… eek) and who loves her for her “sad eyes” – if your mother didn’t warn you about men who say that, let me take the opportunity to do so now. It’s no wonder this lot can be done away with so quickly, the question is why Jenna bothered with them in the first place. And that’s without adding the character sketches for her friends’ partners, who are also awful. Concluding with the owner of the diner Jenna works in, who ends up as her fairy godfather (sigh), the show’s wish- fulfilment ends up more than just silly. Jenna gets on in the world not through her cooking skills but by being the owner’s friend. Contrary to all intentions, we end up with a dumb waitress.

Until 19 October 2019

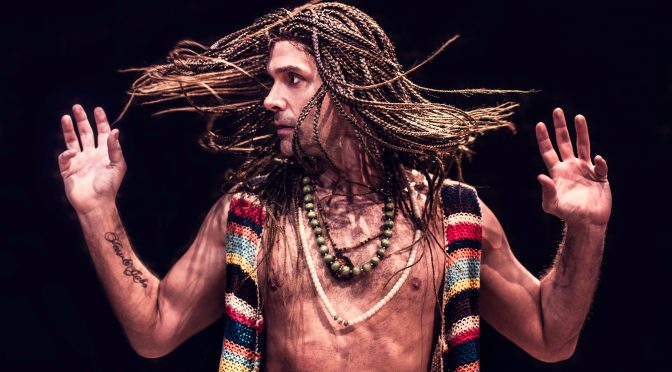

Photo by Johan Persson