Many would rather die than see Ghost. A West-End musical that’s blatantly yet another attempt to cash in on the popularity of a movie that wasn’t very good in the first place, it sounds strictly for out-of-towners. Yet Ghost has some serious talent both behind the scenes and on stage. While its trite tagline asks us to ‘believe in love’, should we believe that this Ghost is worth seeing?

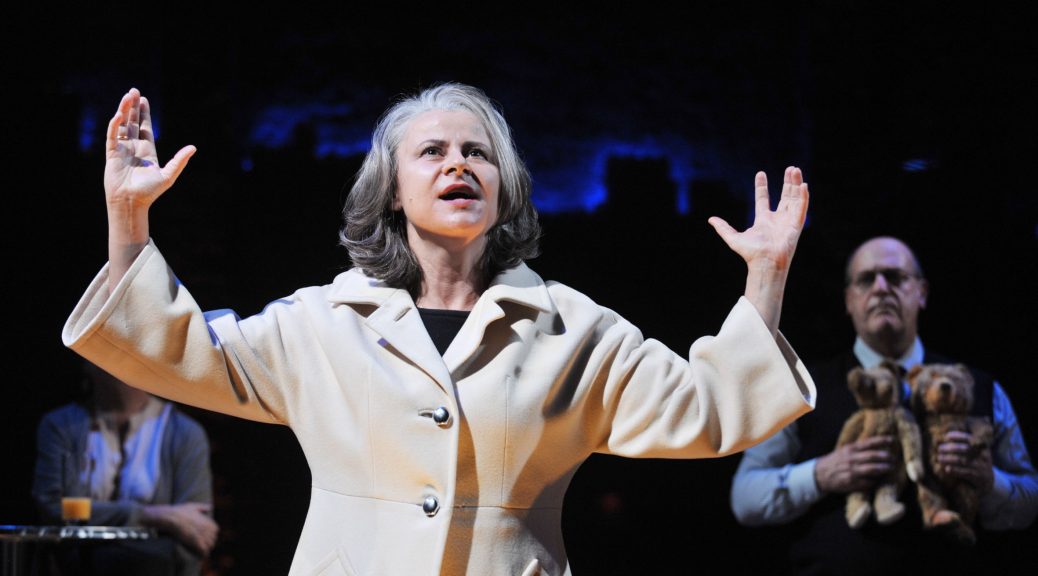

The plot is a given. A young woman becomes haunted by the ghost of her fiancé after his murder, aided by a medium who discovers, to her surprise, that her gifts are genuine. The first coup is the casting of Sharon D Clarke, who has fine comic skills and the kind of voice that makes you suspect she’s too good for the songs she’s singing. Which is certainly the case with the star of the show, Caissie Levy, who plays the lead role of Molly. A performer from America with the kind of belting voice and acting skills Broadway produces so well, Levy is a real star.

The important thing about Ghost is that it contains original music. There are occasions – such as the trio finale of the first act – that are very good indeed and, if some numbers fail, I think Dave Stewart should be given a break, as writing for this must have been a thankless task. With the ‘theme’ from the Everly Brothers already in so many heads, anything else penned is bound to seem incidental. Yet Stewart has produced a score that is interesting and deals with that tune intelligently.

Talented director Matthew Warchus adds credibility to the project and his speedy handling of the story is commendable. But the show seems hampered by flashy projections and the ensemble underused. It is tempting to imagine Ghost as some kind of chamber piece and possible to see that a stripped-back production could have been something very different indeed. The illusions added to the show by Paul Kieve are spectacular and the projections mark a new high technically, but both achievements move the production uncomfortably close to its cinematic heritage and make it strangely untheatrical.

That Ghost is so technically accomplished will not seem a fault to many. But the role of the leading man is a flaw that should have been corrected. As the programme reminds us, the departed fiancé, Sam Wheat, joins a long line of supernatural characters in plays. Unfortunately, Sam has the distinction of being the most boring ghost in theatre history. Richard Fleeshman deals valiantly with this fact, seemingly under the impression that if he sings loudly enough we will forget his character’s insipid sentimentality. He is mistaken. It is difficult to believe Sam is the grand passion of the rather wonderful Molly – love may be blind but here it is in danger of ending up deaf as well.

It is difficult to care about this ghost, so should you bother to see him? Yes. After all, any belief takes a leap of faith and the power behind the central performances, along with the competence of those who have put the show together, should be more than enough to convert all but the most cynical.

Photo by Sean Ebsworth Barnes

Written 30 September 2011 for The London Magazine