This strong new musical from Jon Brittain and Matthew Floyd Jones is quirky and has lots of laughs, with both its originality and humour boosted by excellent performances. Smart and entertaining, it offers something different while maintaining wide appeal.

We follow the adventures of schoolfriends Kathy and Stella, whose true crime podcast goes viral when they become part of a murder story themselves. As amateur sleuths, with little ability and a morbid streak, they provide a lot of grisly fun. But, although he plots well, Brittain’s book for the show isn’t really about crime. The focus is female friendship.

Support given in the battle against low self-esteem is explored in depth to great effect. The show isn’t afraid to poke fun at its heroes, and the performers show an admirable lack of vanity… But you don’t laugh at Stella and Kathy – you want to be their friend. The show’s success rests on performances with real heart from Bronté Barbé and Rebekah Hinds.

There are more than a few sweet moments, a nice surprise given that the show is ostensibly about a serial killer. But Kathy and Stella Solve a Murder! is also a strong satire. Brittain has plenty to say about the true crime genre, and is suspicious, if never vicious. So, while fangirl Erica is a great chance for Imelda Warren-Green to show how brilliantly funny she is, the character is more than just a gag. And celebrity writer Felicia, played with suitably larger than life touches by Hannah-Jane Fox, is such a big character she gets to appear in three different versions. It’s a great way to keep cast numbers down while giving her the air of Cerberus! And don’t worry, Brittain is aware of how much his own show gets from the genre. Maybe it’s worth pinpointing that it’s the internet that’s really in the crossfire – and when you’re in a theatre, enjoying something live, that always feels good. An easy target, maybe, but Stella’s solo about validation is excellent – a theme for our times.

Floyd Jones’ music is good, perhaps serviceable rather than memorable, but the main theme is catchy, with just enough variety. And the songs are impressively ambitious, requiring extremely strong voices, which Barbé and Hinds certainly have. The lyrics by from Floyd Jones and Brittain are excellent – consistently strong, funny and surprising. There are some brilliant rhymes, not least on Felicia’s surname. Even the swearing is smart. Expletives aren’t thrown in for a cheap punchline – they are used often but wisely. And we get the best use of lesbianism in a lyric since Jerry Springer the Opera… and I’ve been waiting to write that for a long time.

There are jokes about pretty much everything in Kathy and Stella Solve a Murder! With a great use of northern accents, both Barbé and Hinds are very funny. They get the most out of every line with impeccable timing. But behind comic characters, full back stories lead to a detailed portrayal of two young women who are both a little lost. It’s hard to escape the suspicion that Barbé and Hinds are best friends in real life. The chemistry here is among the most convincing I’ve seen on stage and is something special to behold.

Until 14 September 2024

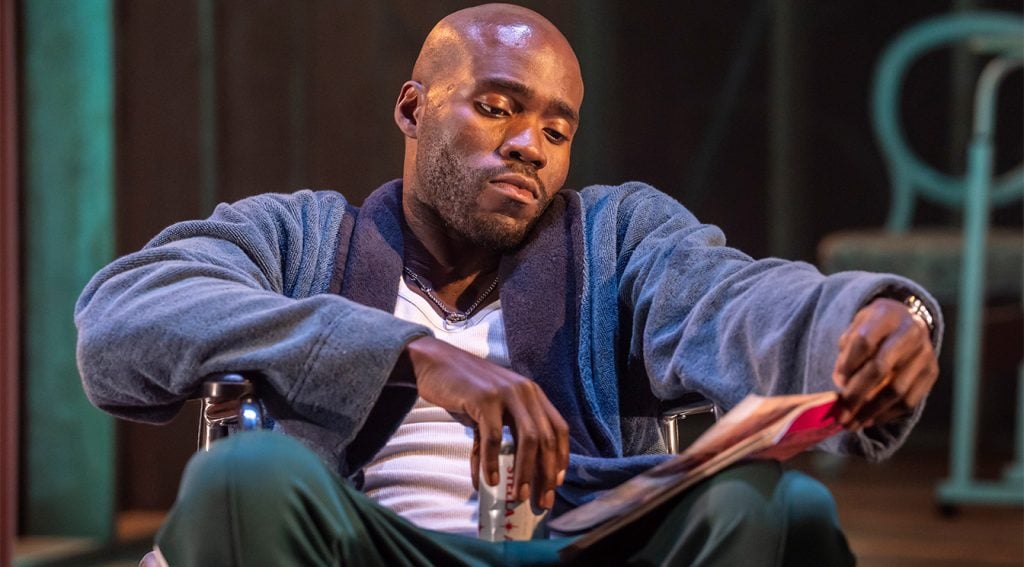

Photo by Ellie Kurttz