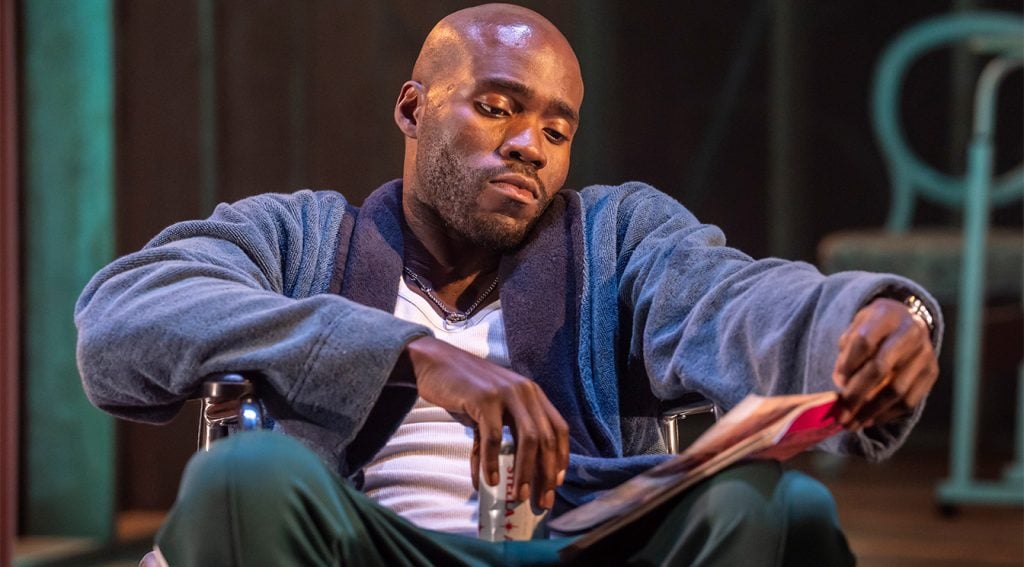

Danny Sapani’s star performance makes Stephen Adly Guirgis’ play fly. The script, neatly directed by Michael Longhurst, is a quality affair: considered, solid, maybe a touch slow to start. Sapani makes the most of the play’s strong moral dilemma and brings out the text’s focus and intrigue.

Sapani takes the part of Walter ‘Pops’ Washington, a former black police officer who was shot by a white rookie while off-duty. How’s that for a smart take on police violence? And if you think it needs a twist, well…Guirgis’ plotting is so strong it doesn’t deserve a spoiler.

Black, white, blue, and green

An eight-year battle for compensation brings money into the mix. Although Washington stresses his motivation is a matter of principles. Add his wife’s death and it’s no surprise our hero has been left a mess. Or has he? Maybe…he was troubled before. Throughout the twists Sapani commands attention. He is believable as both stubborn and dignified, gruff, yet loveable, easy to dislike and winning admiration. Washington is a strong creation, brought to life with style.

Unfortunately, the main character overwhelms the show. Other roles – all well-acted – don’t just pale, they fade away. Washington’s misfit family come too close to caricature. There are funny moments, with strong performances from Tiffany Gray and Ayesha Antoine. And moving ones, played by Sebastian Orozco and Martins Imhangbe (the later especially strong with a great mix of anger and frustration). But they are all just foils, circling around the central figure.

For a London audience, Sapani’s recent role as King Lear will spring to mind. Especially as the character’s rent controlled apartment is under treat and his kingdom about to disappear! Indeed, Washington’s ironically regal touch makes for great moments. But it’s the differences that are more interesting and come in the form of former colleagues, capably played by Daniel Lapaine and Judith Roddy. Their efforts to persuade Pops to settle his law case are strong scenes. Longhurst brings out considerable momentum. They show us different power dynamics, with a balance of discomfort and humour the whole show aims for but isn’t always present.

Until 15 June 2024

Photos by Johan Persson