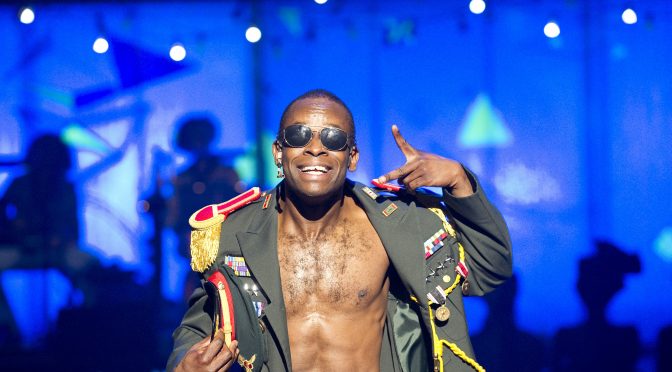

Fela! arrives from Broadway with much fanfare and celebrity endorsement. The story of Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, legendary Nigerian musician and political activist, even has its own exclamation mark – which at least saves me from adding one. Like Fela’s life, this show has a spirit of revolution and is filled with so much energy it will take your breath away.

Fela invented Afrobeat, a musical genre of great sophistication enriched by the heritage he embraced. A potted history lesson at the start of the show sets this out clearly and, even if the songs aren’t to your taste, the performance of them is so electric they are sure to win you over.

Not everything about the show works: direct addresses to the audience and an attempt to give a dance lesson fall rather flat. Even if a British audience does join in, they don’t really want to. There must also be a worry that, given the average age of the patrons at a National Theatre matinee, attempts to shake hips during afternoon shows might well result in serious injury.

Thankfully Fela! is not just a tribute show. The music is superb and the choreography by director Bill T Jones is stunning, but it is the story that surprises. As Fela is about to leave his country after suffering political persecution, he has to justify his actions to himself and to his dead mother, Funmilayo Anikulapo-Kuti (Melanie Marshall), who was an inspirational figure. We also meet another important woman, the American Sandra Izsadore (Paulette Ivory), who furthered his political education. The performances from both women are outstanding and their voices sublime. Exploring these relationships makes for riveting drama.

As Fela recounts his own life, the tendency to hagiography is inevitable, but this is clearly signposted. Sahr Ngaujah, who originated the title role on Broadway, treads the fine line between showing us a real person as well as revealing a genius. It is a performance showing such talent it becomes easy to see why so many followed Fela and so great you will be tempted to do the same.

Until 23 January 2011

Photo by Tristram Kenton

Written 17 November 2010 for The London Magazine