Playwright Drew Pautz has set himself a challenging task in writing Love the Sinner. His new play, premiering at the National Theatre’s Cottesloe auditorium, takes as its subject matter internal politics within the Anglican Communion. This is not, for many of us, the hottest of topics.

Thankfully, the play opens up rather beautifully. The debate, taking place in Africa, questions the role of religion in the modern world. The African delegates stand in contrast to their European counterparts. For them, religion is a powerful force, and they have a faith that might be commended by Kierkegaard. The church should take a stand – preservation not progress is needed. Discussions are ostensibly about the rights of homosexuals in the church and, when a volunteer at the conference has a sexual encounter with one of the hotel’s porters, Pautz begins to explore how abstract arguments impact on personal conscience.

Jonathan Cullen plays Michael, the volunteer who finds himself in a distinctly awkward post-coital conversation with a hotel staff member. Joseph, touchingly insistent on his name being remembered, is desperate and dangerous. Described subsequently as a Furie, Joseph is played by Fiston Barek with a febrile energy. Cullen, by contrast, risks being too meek to be believable.

Anxiety follows Michael back to England where, to the detriment of all, religion becomes an increasingly important part of his life. Charlotte Randle is a highlight as his wife Shelly. So obsessed with having a child that having a husband seems an annoyance, she is exasperated by the man she now lives with who, seems to just ‘sweat and pray’. As the distance between them grows, Randle crafts a moving portrayal. At work, a skilful mix of embarrassed glances and confrontations make for an amusing farce whose comedy is tempered by melancholy. And Michael’s problems have really only just begun.

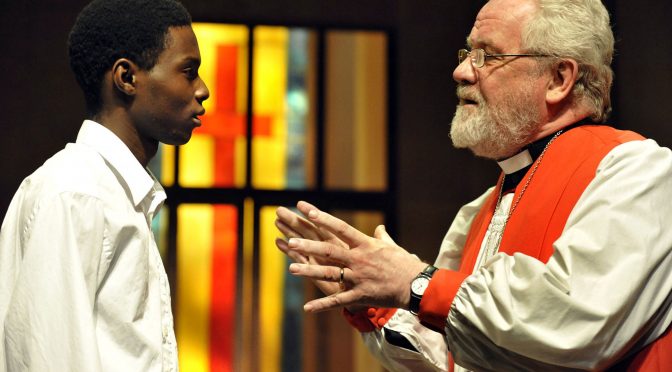

Joseph finds his way to England and Michael providing a skilfully written, tense final act. Here, Scott Handy is superb as the church’s PR man who sees realism, not God, in a situation, while Ian Redford does well as the play’s liberal bishop.

What the Bishop and Michael both want is reconciliation. An agreement, at least, to disagree. Throughout the play, such a step seems impossible and, if God can’t provide it, then it is unreasonable to expect that Drew Pautz can, no matter how satisfying it would be for an audience. The effort made by Joseph to progress past the shame he is supposed to feel ultimately fails to convince. It seems inevitable that this thought-provoking play leaves us feeling unreconciled and unresolved.

Until 10 July 2010

Photo by Keith Pattison

Written 13 May 2010 for The London Magazine