This new musical boasts lots of talent – that delivers – but, regrettably, fails to excite. The excellent Kwame Kwei-Armah directs an incredible cast with a book by Sarah Ruhl and music and lyrics by superstar Elvis Costello. Naturally, expectations are high, and everyone does a great job, but the show is effortful rather than inspired.

Having a film in the background might not help, although Ruhl has adapted Budd Schulberg’s book as well as the screenplay that Elia Kazan used. But that was back in 1957, and the story has dated badly. The larger-than-life character of ‘Lonesome Rhodes’, one time down-and-out, then a TV star who tries to get into politics, sounds as if it has potential, but falls flat. Truth has proved stranger than fiction and a plot that should be fantastical feels old hat.

The action is admirably swift. Although Lonesome’s rise and fall is quick, Rhul and Kwei-Armah examine his psychology thoroughly. There’s a sense of outrage as we move from folksy philosophy to sinister popularism. And the character is intriguing, if predictably hypocritical: viewed by his fans as a mix of Jesus Christ and Santa Claus, he’s big on the state of Arkansas and the state of matrimony. But if the jokes don’t make you laugh out loud, I’d suggest the same problem – none of it is as crazy as real life.

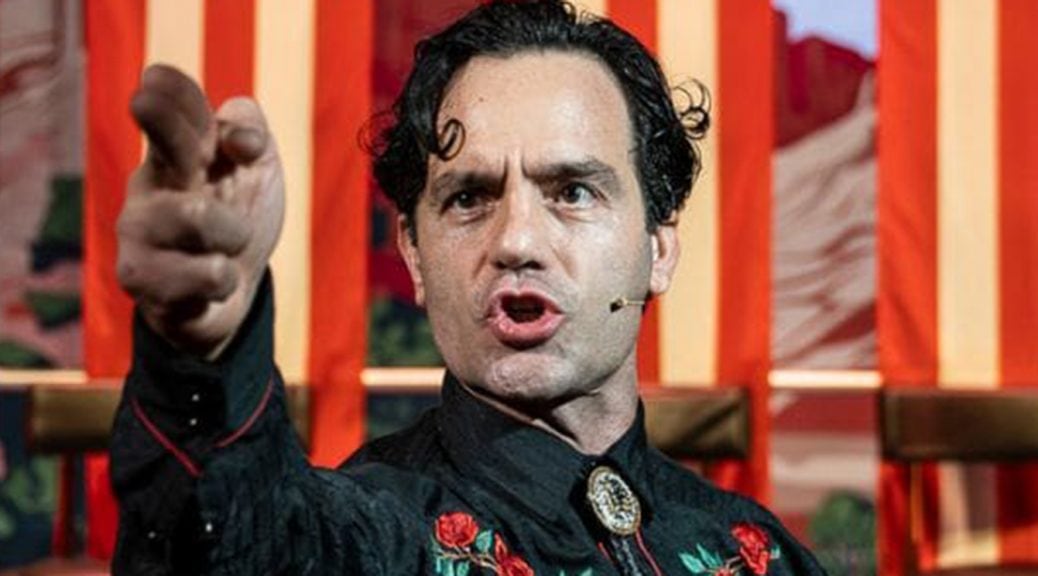

Lonesome is at least a great role for Ramin Karimloo, who sounds fantastic. There’s superb support for him, too. Firstly, from Anoushka Lucas, a radio producer called Marcia who discovers Lonesome and might, almost, steal the show. Marcia gets the best numbers, which Lucas performs beautifully. Her attraction to her protégé might be given more time but a second love interest for her character (played by Olly Dobson) does well – neither character is simply a foil.

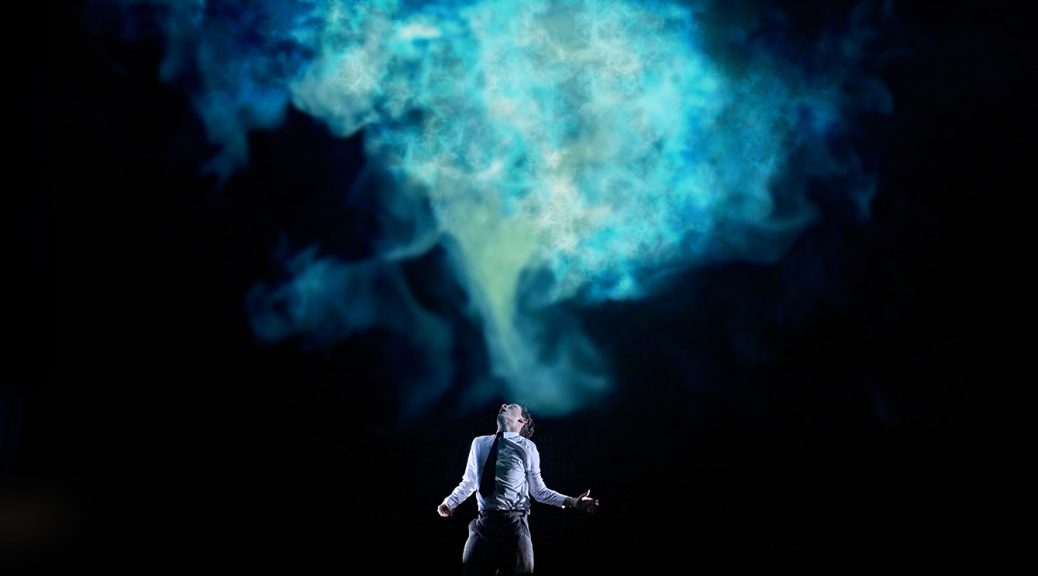

The cast could be bigger and the choreography (Lizzi Gee) more ambitious. But Elvis Costello’s music – pure Americana – will please many. Some of the songs are superb, especially the title number, and the mix of country and jazz is intelligent. It’s a shame the ensemble doesn’t sing together more. And that the advertising jingles are such predictable interludes. If the score doesn’t work quite like a musical, it sounds different and I’m sure a soundtrack would sell.

Still, the show is hard to recommend. Even if Lonesome as a kind of early influencer interests you, the piece doesn’t situate itself well in history. It’s never quite clear what year we are in (and the costume design doesn’t help). But the biggest problem is that the satire is just too tame. And although Karimloo has charisma, his character’s popularity doesn’t convince. It is too easy to explain the confluence of politics and entertainment with ignorance. There is a danger the show becomes as contemptuous of the public as Lonesome is… and that suggestion loses my vote.

Until 9 November 2024

Photos by Ellie Kurttz