Theatrical responses to young adult mental health hit the big time with this highly anticipated tear-jerking transfer from Broadway. Teen suicide and all manner of problems for millennials make the target audience sometimes painfully clear. But there’s an intelligence behind Steven Levenson’s excellent book that raises Dear Evan Hansen well above many coming-of-age dramas.

The action revolves around social media (these kids are more online than at school). Tension mounts as Evan’s deceit, about his friendship with deceased class mate Connor, entangles him in the world wide web. A campaign, including Kickstarter, and the inevitable empowering vocabulary that follows, is treated with a mature, sometimes sceptical, touch.

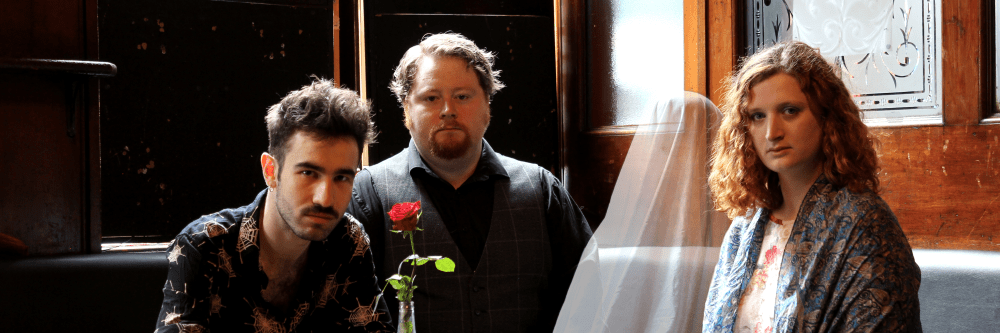

Connor’s death is the best thing that’s happened to Evan; he finally has a profile at school. But the friendship it engenders is an imaginary one with the dead boy. Meanwhile, contact with Connor’s sister results in a clever twist on Cyrano de Bergerac that’s heartbreaking. Along the way, the roles provide strong parts for Doug Colling and Lucy Anderson, who contribute to the uneasy atmosphere that Michael Greif’s direction explicates. As Evan promises his lost and lonely cohorts “You Will Be Found” – becoming an internet hit himself – the drama that he will be found out is considerable.

The story may be simple, even predictable, but it broadens gracefully. Becoming a show that concerns mourning and parenthood, there are well-drawn roles for the adults in the piece. Unashamedly, rather than learning from themselves or their peers, they are the characters for their children to learn from. Rebecca McKinnis is superb as Evan’s struggling mum, while Lauren Ward and Rupert Young play Connor’s grieving parents with believable intensity. All three are included in scenes of psychological complexity that ensure depth.

Scenes of extended dialogue mean that Dear Evan Hansen is – almost – as much a play with songs as a musical. The show has its own pace, handled boldly by Greif, that is distinctive. The numbers by Benj Pasek and Justin Paul are already hits, so whatever formula they have for bringing on the tears is clearly effective. The music is good, although more of it, as well as more variety, would be welcome. And the lyrics are superb – not a word jars.

These numbers are not easy to perform. As well as demanding considerable acting skills, the score acts symbiotically with the performances to make the show increasingly impressive. The same pressure makes the title role especially exciting, as you need a superb singer and a strong actor. Ticking both boxes, the part of Evan is sure to make a star of Sam Tutty. While the show is more of an ensemble piece than you might expect, the role of Evan is crucial. Again, Levenson allows a considerable complexity that Tutty can develop: this isn’t your average hero, or even your everyday misfit. The balance to retain sympathy for Evan proves fascinating.

If the conclusion of Dear Evan Hansen is a little pat, it is also impressively understated; any positivity isn’t cloying. Hope for the future is the best that can be offered, maintaining a distinctly melancholy air. Seclusion is the prevailing theme; which is especially sad as you never forget this is a show for young people. Thankfully, support and a sense of perspective are present – they give the piece an underlying wisdom. And the show’s success provides inspiration; the audience response, amidst much sniffling, is contagious. Deservedly, lonely Evan Hansen should prove to be a long runner.

Until 30 May 2020

Photos by Matthew Murphy