The theatre world often fantasises about the next big British musical, and a home-grown piece is always something to celebrate, so this work, spearheaded by composer and lyricist team Tim Phillips and Marc Teitler, has arrived from Bristol to the West End like a dream. The Grinning Man is original, polished and has a sense of integrity that, while making its success cultish rather than mainstream, wins respect.

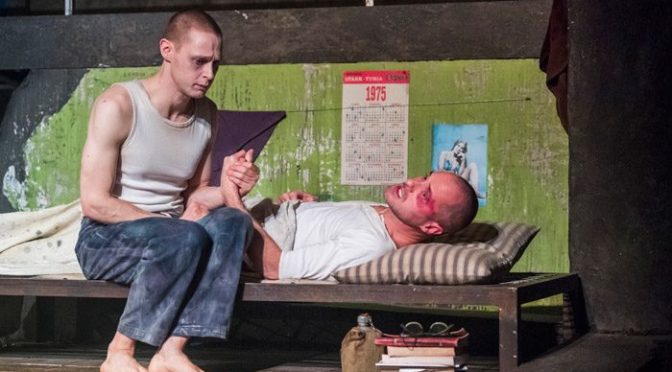

The story is a fairy tale, heavy on the Gothic, but for grownups. Set in a familiar work, although with surprisingly little satire, our eponymous hero was disfigured as a child and is now a circus freak show. It’s a star role that Louis Maskell delivers with conviction. With a blind girlfriend and sinister adopted father in tow (Sanne Den Besten and Sean Kingsley), the much sung about “ugly beautiful” appearance of this charismatic changeling alters society for the better. The colourful royal family, with a strong quartet of performances from Julie Atherton, David Bardsley, Amanda Wilkin and Mark Anderson, all fall under his (inexplicable) spell. The only one on stage who seems immune is a villainous jester, for my money the lead of the show, brilliantly portrayed by Julian Bleach and winning most of the laughs.

The tale is as good as any by the Grimms. It’s based on a novel by Victor Hugo, and writer Carl Grose tackles it well. But the swearing, nymphomania and a bizarre incest plot make it adults only. It’s something of a puzzle – the temptation to appeal to a larger audience must have been great. A bigger problem is that the score only interests by including some bizarre electronic sounds and the songs aren’t catchy enough. While the dialogue is good, the lyrics, from Phillips, Teitler, Grose and also the show’s director Tom Morris, are too often uninspired.

Yet the production itself is an unreserved triumph. There’s fascinating movement and choreography from Jane Gibson and Lynne Page, accompanying Morris’s strong direction. And when it comes to portraying the worlds of circus and court, Jon Bausor’s design is magnificent. There’s a lot of puppetry, superb in design and execution, complemented by sets that are like a trip to Pollock’s toy shop. Topping it all, with a range of influences from steam punk to Gormenghast, are terrific costumes by Jean Chan. It’s the attention to detail, the look of the show, that puts smiles on faces.

Until 5 May 2018

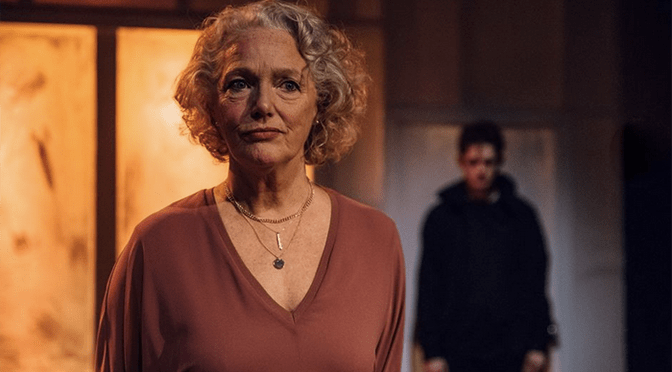

Photo by Helen Maybanks