Emma Rice’s second, and sadly final, season as creative director on the South Bank opened last night with a bold, experimental show directed by Daniel Kramer. Not for all tastes, and far from flawless, the production brims with intelligence as well as tricks – if originality is what you seek, it is plentiful.

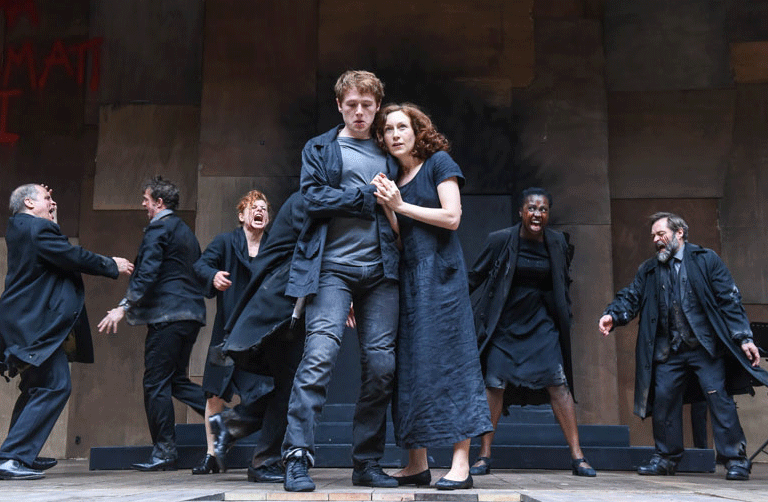

The Montagues and Capulets are made up like clowns – “alike in dignity” indeed. Missiles hang in the sky and coffins abound as doom and death pervade the arena. Subtle it ain’t. Nearly every line is wrung for all its worth, with exaggerated delivery or incidental action. Even Romeo changing his trousers can mean missing a plot point. It’s exhausting, but always engaging. And such bombast makes the masque scene unmissable: karaoke ‘Y.M.C.A’? Why not? And Mrs C’s Fay Wray fancy dress is to die for.

Some of Kramer’s ideas are a puzzle. Why does Lady Capulet double as the apothecary? And why are there so many guns when knives and poison are specified? Other ideas have unfortunate consequences: the make-up and incredible costumes, a cohesive part of Soutra Gilmour’s design, make it difficult to differentiate characters. Which leads to the production’s biggest fault – a sense of performers struggling to stand out, leading to a kind of hyperinflation.

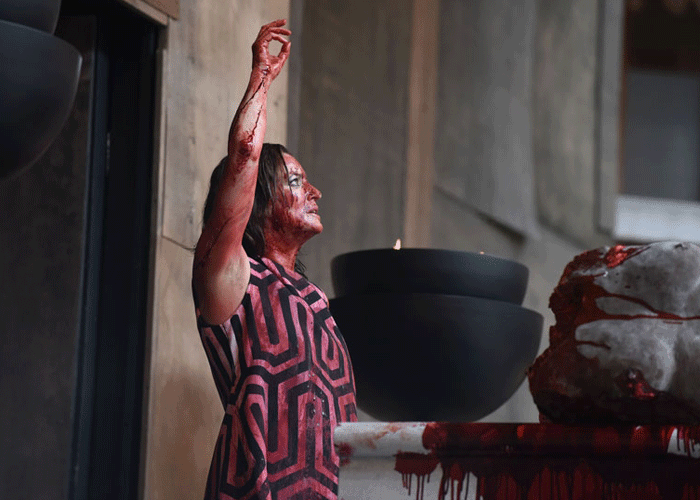

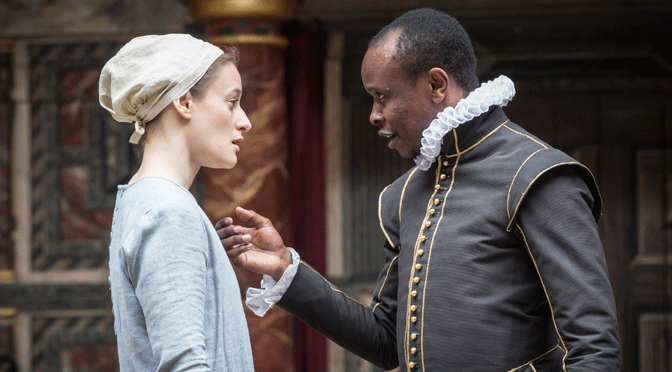

The notable exception is Golda Rosheuvel’s Mercutio, whose recasting as a woman adds tension to her friendship with Romeo. Rosheuvel embodies Queen Mab in unforgettable fashion and her death scene is shocking. In the title roles, Edward Hogg energetically follows Kramer’s strategy, using every inch of the stage. Kirsty Bushell’s Juliet is more captivating. The lovers present some of their venerated lines as hackneyed – a startling move that accentuates the often ridiculous and embarrassing nature of teenage love.

Kramer’s vision of the play is bleak right to the end –it’s about dying kids, after all. Anger fills the show, with a lot of running around. There’s a fantasy execution of parents and in-laws by Romeo, and Juliet’s lust is violent, too. Both scenes are riveting. The only quiet moment is the marriage night, during which Bushell and Hogg magically introduce a sombre tone. These lovers are more star defying than star crossed, leaving little room for any other emotion.

Kramer’s most exciting idea is conflating scenes. Joining Romeo and Juliet’s marriage with Mercutio’s fatal encounter with Tybalt adds poignancy. Playing scenes two and three of Act III simultaneously creates a riff on the theme of banishment and death that is inspired. It’s a shame these interpretations are more successful than the production’s emotional impact. Yet they are brilliant insights, shaping the way we see the play and, in my eyes, redeeming many of its faults.

Until 9 July 2017

Photo by Robert Workman