The last London outing of Peter Shaffer’s 1973 play boasted exciting star casting. But even the presence of Daniel Radcliffe, who did a great job playing the stable hand Alan who blinds the horses in his care, didn’t quite distract from the dated manner of this psychodrama. Equus can be a laboured whydunit, as the aloof Dr Dysart lags behind the audience in reconstructing events and struggles to provide an explanation for an all-too-symbolic outrage.

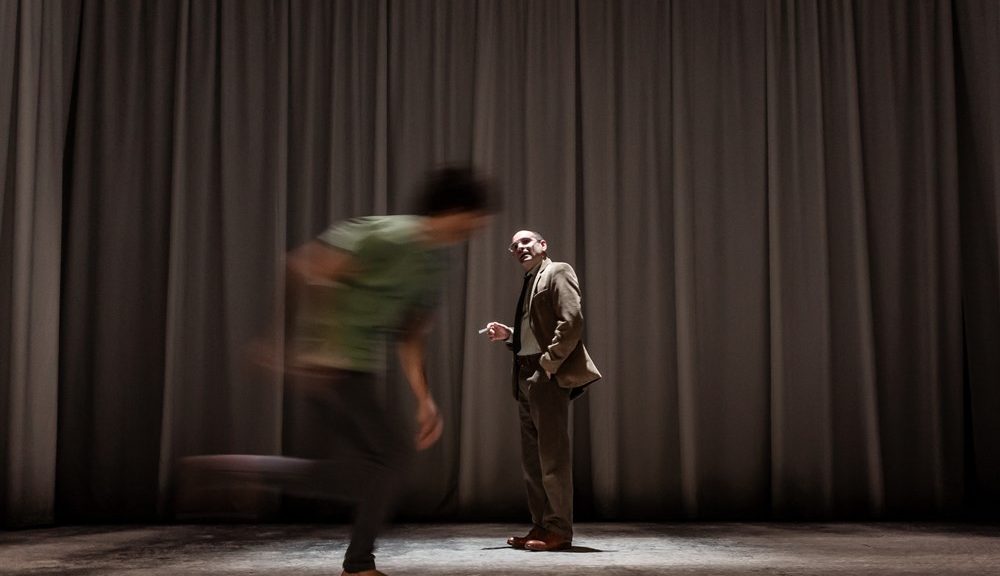

In this new production, director Ned Bennett gallops over many flaws, adding a physicality that balances the theorising monologues. Meanwhile, the lighting and sound design, from Jessica Hung Han Yun and Giles Thomas respectively, add psychedelic flashes of light and bursts of sound to great effect. With a strong cast, dashing on and off stage with unnerving speed, the piece is served superbly – this is one of the best revivals you’ll see in a long time.

The play’s problems are still there, of course. A contemporary audience is probably too used to tracing trauma – and too familiar with psychobabble – to find such a quest revelatory. But Bennett manages to make it exciting. The clever move is to focus on the doctor, played superbly by Zubin Varla, as much as the patient, and to make the philhellenic clinician’s dissatisfaction with his own life a source of questions. With increasing distress, Dysart sees his treatment will deprive Alan of a life-enhancing passion – the key word is worship – which is a challenging proposition, given Alan’s actions. Varla provides convincing fervour, and plumbing Shaffer’s text to bring out the theme works well.

The production flirts with a period setting, sometimes to its detriment. Georgia Lowe’s minimal design of clinical curtains is used to great effect, but the costumes, as a nod to the 1970s, are confusing. And too little is done about the female roles. Norah Lopez Holden, who plays Alan’s love interest, feels so contemporary she could come from another play. While Alan’s mother is in 1950s mode with Syreeta Kumar’s oddly wooden depiction.

The cast is superb though when it comes to doubling up as the horses, led in this endeavour by Ira Mandela Siobhan. Avoiding fancy puppetry emphasises the sensual to an almost risqué level – the show is confrontationally sexy. For a final exciting element, there’s the performance of Ethan Kai as Alan. Theatregoers love a career-defining role and this surely counts as one. As well as creating sympathy for the character – no easy leap – he also makes Alan scary. Presenting a young man so dangerously unaware of his own strength, Kai allows Alan to stand as an individual rather than an object in Shaffer’s intellectual game – and all benefit as a result.

Until 23 March 2019

Photo by The Other Richard