If your life has been even vaguely touched by the tragedy of child abuse, then this new play by Bruce Norris will be difficult to watch. The scenario of four men on the sex offenders register in the US living together on probation is an unpalatable subject matter for most. But theatrically Norris and his team from Chicago’s prestigious Steppenwolf Theatre have achieved the improbable – creating a kind of sympathy for these men and making great drama as a result. The provocative strategy has a further use – creating an empathy for people we find repulsive allows big questions to be asked with challenging clarity.

Justice, with the dichotomy of punishment versus vengeance, is the theme. And it’s complicated by the need to continue to protect children that the men now live near. We see two sides of contrition, in the roles taken by Eddie Torres and Francis Guinan, both equally questionable and powerful. All this might be considered a timeless dilemma. But Norris also addresses a particularly topical concern – ideas about trauma and victimhood particular to our times – with remarkable bravery. Giving a voice to the abusers is a bold move. The reasoned arguments, presented with wit or religion respectively by the characters K Todd Freeman and Glenn Davis so brilliantly portray, are remarkable. The tension with our distrust of these men is wonderfully handled.

Along with these personal debates, we encounter the judicial system, represented by probation officer Ivy, brought to the stage so vividly by Cecilia Noble. There are practical touches and legal constraints to Ivy’s generally sympathetic approach to the men, as well as utterly credible touches of exhaustion. But the play’s real originality comes with scenes of a victim confronting his abuser. Andy, played with such care and skill by Tim Hopper, shows a brittle calm presenting rote-learned arguments arrived at via his therapy. It’s almost unbearably tense at times and incredibly sad but, importantly, thought provoking.

The writing is close to flawless, so it’s a shame that one plot twist is over prepared and therefore not quite as shocking as intended. Meanwhile, the performances are perfection and director Pam MacKinnon deals with the actors and the subject matter with utmost care. Without degrading Andy’s trauma, and getting considerable dramatic tension from the idea that we cannot trust these convicted felons, Norris leaves open a judgement as to a statement that victims don’t lie, with the suggestion that there are degrees of trauma that victims as much as the law fail to take into account. It’s a suggestion uncomfortably out of kilter with our times and surely important to raise for that very reason.

Until 27 April 2019

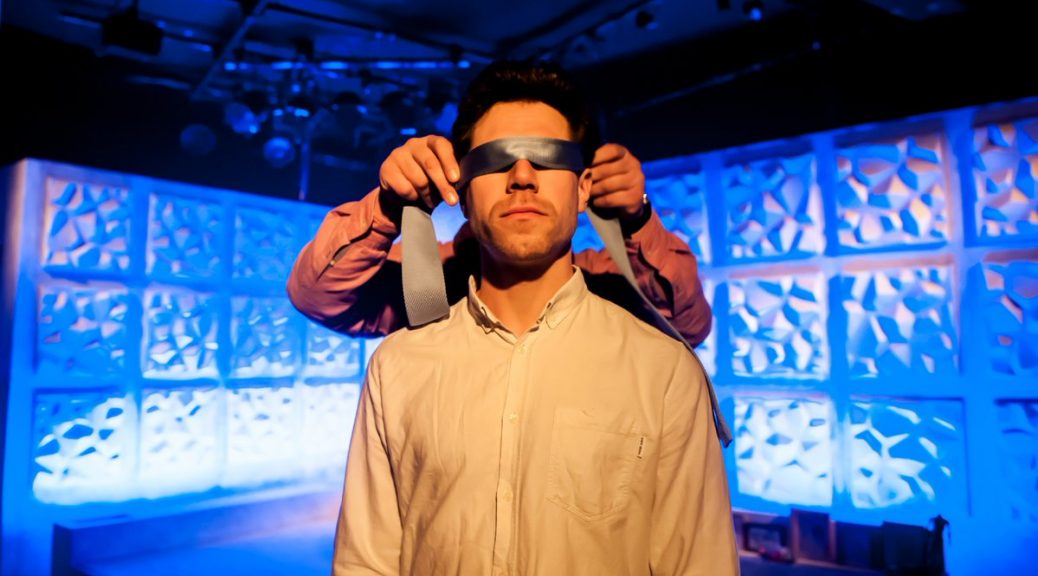

Photos by Michael Brosilow