One of the smallest venues in London – surely in desperate need of the donations requested while making this production available online – the Finborough’s prestigious reputation is lived up to in artistic director Neil McPherson’s play. Taking the life of World War I soldier Charles Hamilton Sorley, it makes appropriate viewing during the weekend of VE day: a moving tribute to lives lost in any war and – in particular –to one admirably independent, and therefore challenging, young man.

First seen in 2016 and justly receiving critical acclaim, including a nomination for an Olivier Award, McPherson’s play mingles the poetry and letters of his subject confidently, and director Max Key complements his careful editing. The same expert touch comes with the show’s music, directed by Elizabeth Rossiter, who performs on piano accompanying tenor Hugh Benson.

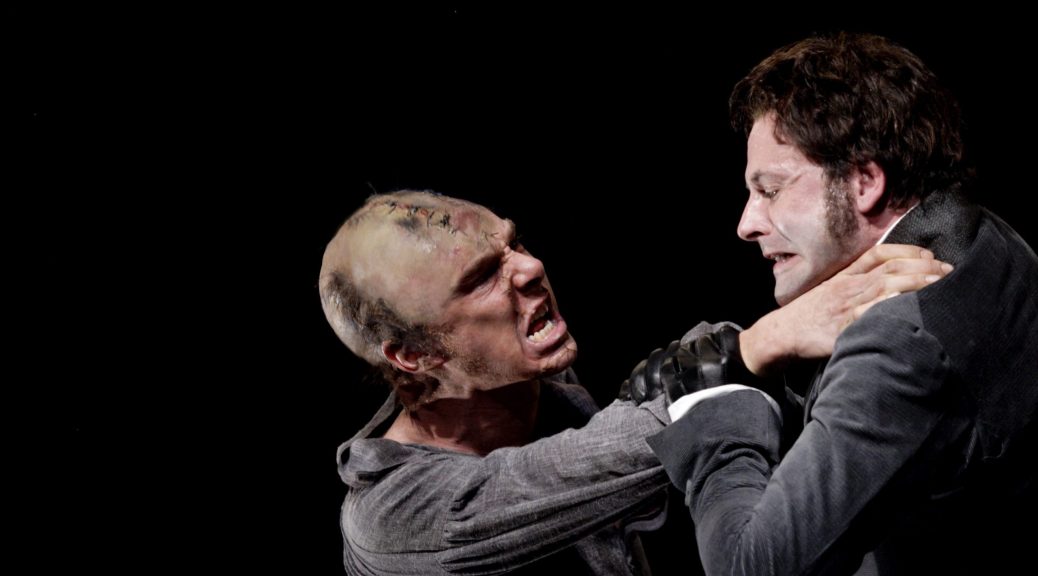

McPherson’s structuring of the play could serve as a lesson to many. Time is taken for us to get to know the subject, one so full of life before his death at the age of 20. When the war comes it is all the more powerful and Key deals well with battle scenes that contain only one man. The projections used throughout the show are frequently lost in this recording, but it is easy to imagine the mounting power as we see the faces and fates of so many of the people mentioned.

There’s a strong sense of period, which never feels forced, shown at its best with the acting of Jenny Lee and Tom Marshall, as Sorley’s parents. Both give beautiful, restrained, performances of roles well filled out. The brief scene of their final goodbye to Charles is brilliant. And debates over whether to publish another “dead public school boy” show the cool intelligence their son inherited. Gratitude that they, and subsequently McPherson with his play, pursued their commemorative project grows.

It Is Easy To Be Dead is a major role for Alexander Knox as Sorley – its success rests on his shoulders. Winning from the start with a schoolboy wish to leave “custom on the shelf”, humour and touches of romance are all conveyed, along with plenty of additional characters. But Knox’s real skill is allowing the true star to be the play’s subject.

Sorley’s words draw us into the action and make us care for him enormously, but it is his common sense – over sentiment and even patriotism – that really impresses. Calling the conflict the “joke of the century”, claiming that of 12 million combatants only 12 really want to fight, his fury against “deliberate hypocrisy” (and critique of Rupert Brooke) are refreshing and much needed. As a final tribute, Knox’s readings of Sorley’s poems do them justice – surely a poet could wish no finer tribute.

Available until 7 July 2020

Photos by Scott Rylander