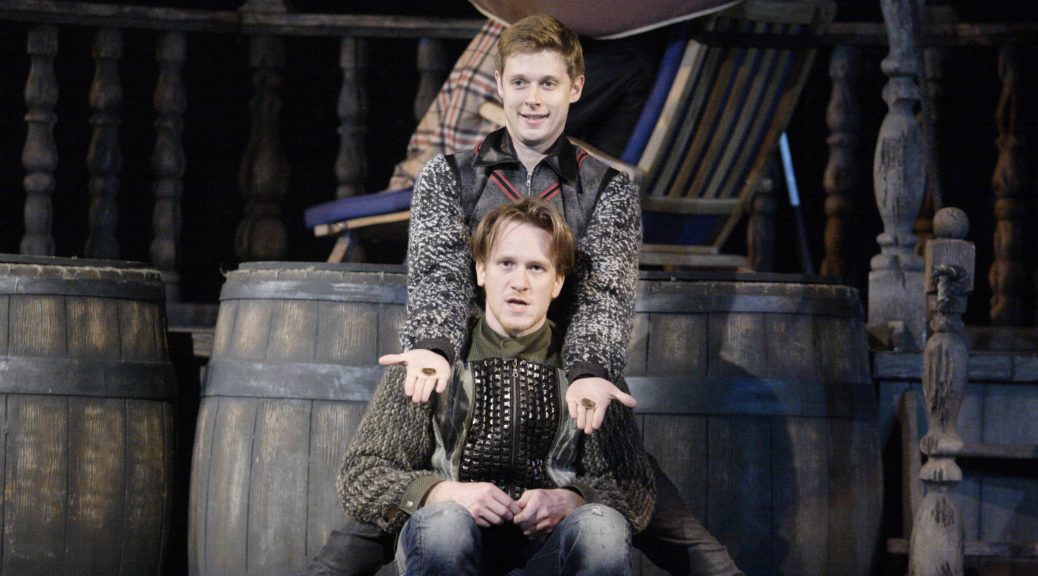

Double Bill, The National Theatre’s programme of four short plays by new writers, finds itself located in the theatre’s paint frame. An impressive working space, it’s a startling location for the pieces: edgy and exciting, this minor reworking of Lasdun’s building does the theatre credit.

First up are Edgar and Annabel by Sam Holcroft and The Swan by DC Moore. Both writers already have exciting reputations. It’s only fitting that the National gives them a platform, and they rise to the occasion.

Holcroft presents a dystopian future with swift precision, turning a political scenario into a domestic drama with such wit and originality it doesn’t deserve a plot spoiler. The eponymous couple have a dark secret that leads to hilarious dealings with a karaoke machine and explosives. In the title roles Trystan Gravelle and Kirsty Bushell deal with their characters’ double lives impeccably.

DC Moore takes us to a more familiar place. The London Magazine readers won’t visit many pubs such as The Swan, certainly not on the occasion of a wake for a crowd like this one, but Moore’s family tragedy contains both compelling humour and drama.

With a star turn from Trevor Cooper as the patriarch Jim, who delivers every line with an obscenity, and a superb cameo from Claire-Louise Cordwell, damaging secrets are hidden to preserve a deeper truth – brought home to us with a little help from Spandau Ballet. Moore’s characters have to be seen to be believed and they are well worth watching.

Both Holcroft and Moore have an unfailing gift for dialogue; vital since despite superb design here, and hard work for the back stage crew whose home we are invading, these are modest productions. The conversations that occur in any relationship when it becomes mundane and the talk you might overhear in a less than salubrious South London local are wonderfully observed and then developed to another level with a mature concern for the truth.

Any institution with the longevity and largesse of the National Theatre will have a chequered history of new writing. Playwrights coming to work there are placed in the spotlight and automatically join a debate about the state of the arts, whether they want to or not. If these first two plays are anything to go by, new writing is in superb shape – Double Bill is an event that one hopes will become a fixture.

Until 10 September 2011

Photo by Johan Persson

Written 5 August 2011 for The London Magazine