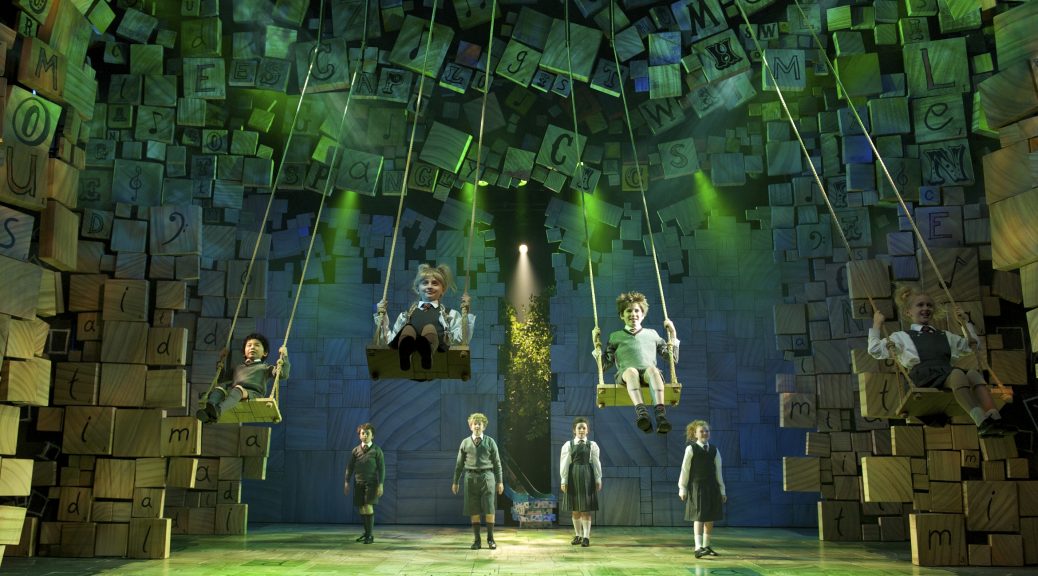

As its history of transfers to the West End and Broadway demonstrates, The Menier Chocolate Factory has an enviable reputation when it comes to musical theatre. This is a team that knows what it’s doing and their new production of Pippin confirms just that. If ‘updating’ a story about the son of ninth century Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne into the computer game era sounds mad, fair enough. But it works to perfection.

The 1972 piece by Stephen Schwartz, now famous for his success with Wicked, follows the eponymous hero’s quest for a meaning in life. Pippin’s efforts to lose himself in fighting, sex or politics, are presented as levels in a computer game. Along the way he is accompanied by the sinister ‘Leading Player’, constantly nodding at a metanarrative that sits happily with the new production’s conceit.

Credit goes to Director Mitch Sebastian’s confidence and determination to follow the idea through. From the zapping noises that greet the audience upon arrival, to the faces of texting monks lit up in the gloom, there’s such attention to detail you can’t help be impressed. Best of all is Sebastian’s decision to base his choreography on the original work by the legendary Bob Fosse. It is the core of the show: bold, articulate and wonderful to watch.

Using computer games to add a ‘boys own’ feel to the show allows designer Timothy Bird’s imagination to run riot with projections as witty as they are dazzling. Similarly, Jean-Marc Puissant’s crazy costumes – part Visigoth, part Tron – are something you won’t forget in a hurry. This is a sexed-up Pippin with an intelligent eye for the crass aesthetics of adolescence.

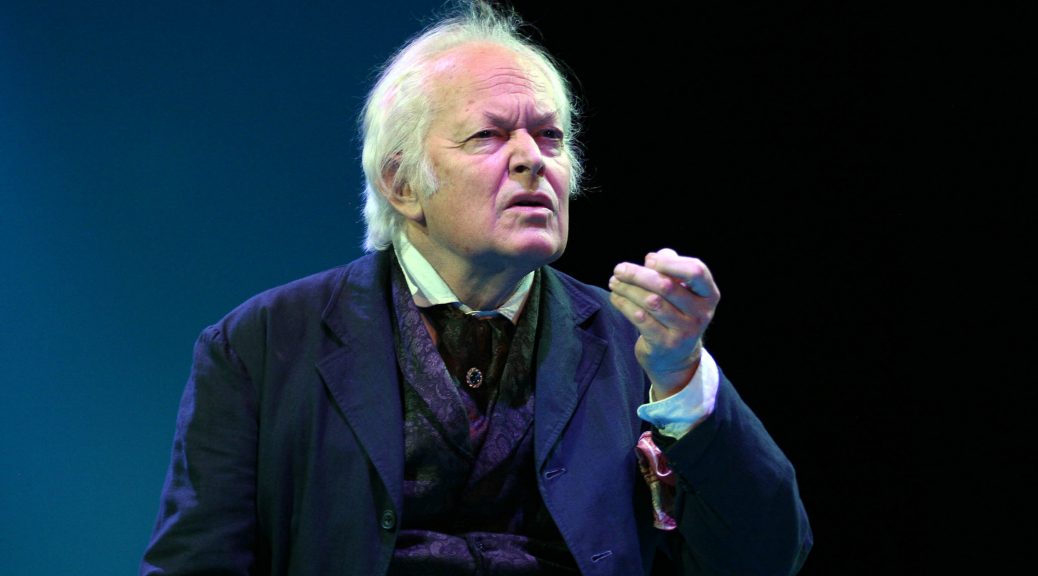

Harry Hepple’s performance as the lead is commendable. With more than a touch of self-pity Pippin’s search to stop feeling “empty and vacant” often seems indulgent but Hepple manages to retain our sympathy and his voice is great. Hepple doesn’t even get a break in the interval as he continues to play his computer game in the corridor as the audience files past. Frances Rufelle’s rendition of Spread of Little Sunshine is revelatory and there is an outstanding performance from Louise Gold as Pippin’s “still attractive” grandmother that is a genuine crowd pleaser.

Pippin is very much a musical lovers’ musical. You need to be able to laugh at lines like, “it’s better in a song”, as well as adoring catsuits and jazzhands. While Schwartz can write a good tune and a serviceable lyric, providing plenty to hum on the way home, much of Pippin is so firmly rooted in the 70s it can be painful. Unusually it is Sebastian and his cast that should get the credit, transforming a musical that could be damned with faint praise into a fantastic night out.

Until 25 February 2012

www.menierchocolatefactory.com

Photo by Tristram Kenton

Written 8 December 2011 for The London Magazine