James Graham has made a strong reputation for himself with plays about politics. While similarly concerned with power, his new work has a broader subject matter and relates the genesis and meteoric rise of The Sun newspaper.

Graham’s nose for a good story is as fine-tuned as any journalist’s. The purchase of an ailing broadsheet by Australian outsider Rupert Murdoch, and the hiring of neglected hack Larry Lamb to run it, take on a mythic quality. These are great roles for strong actors: Bertie Carvel is the ruthless, on-the-up tycoon, while Richard Coyle is the editor whose doubts and determination both mount as he chases sales figures.

The triangle between Murdoch, Lamb and the latter’s former mentor and now rival on The Daily Mirror, Hugh Cudlipp, might have been developed further. There’s an excellent performance from David Schofield as the crusading lefty whose paper aims to improve its readers. An idealistic fourth estate is where politics comes to the fore in Ink and, surprisingly, the play’s very few ponderous moments come from this elision.

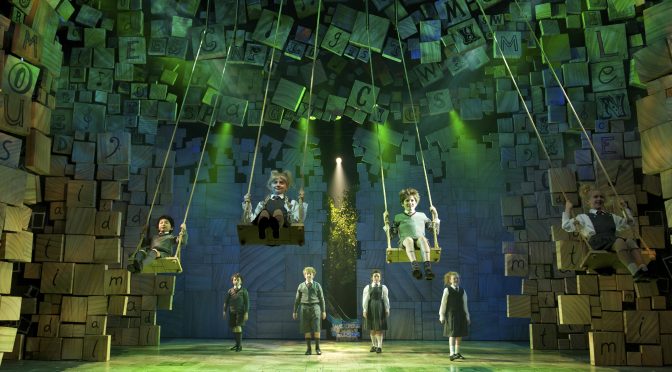

Director Rupert Goold stages the recruitment of staff at the new paper with a cabaret feel: jolly, anti-establishment, with 1960s cool. And Goold handles the play’s darker territory just as well, with a kidnapping and the launch of The Sun’s infamous topless models: a scenario that leads to strong performances from Sophie Stanton as the paper’s women’s editor, and Pearl Chanda as Stephanie Rahn, the first ‘Page 3’ girl.

Newspapers mark a generational divide – the young really don’t read them. Graham’s skill and research bridge the age gap. I wondered if we needed a scene taking us through the printing process (akin to his excellent précis of parliamentary procedure in This House) but, yes, of course we do! With a touch of nostalgia, reflecting several characters’ romantic notions of Fleet Street, an arcane world of machismo and lots of cigarette smoke is opened. Hindsight raises smiles and big questions about media manipulation.

The result of Graham’s fun groundwork is a delicious surprise – a depiction of Murdoch that shows intelligence and courage. With a little retrofitting, Murdoch is cast as a business disruptor and credited with the idea of user-generated content. Neither role is that convincing but the ideas intrigue. Murdoch’s drive, so perfectly embodied in Carvel’s performance, comes from his wish to challenge and change – recasting an often-demonised figure as a rebel with a cause.

Until 5 August 2017

Photo by Marc Brenner