A big hit back in 1949, this psychological drama by Lesley Storm has been revived by director Clive Brill. It’s a quality production and the writing of a high standard. But there’s no escaping that this is a period piece with ideas trapped in their own time.

When a well-off housewife becomes a petty thief a “mind specialist” is called in to help with her legal defence. As a whydunit, it’s an effective premise, if a little simple, and Sharp gives us a close study of family friction that’s nicely delivered by Jack Staddon and Eva Feiler as the son and daughter. It turns out the former is “locked together emotionally” with his mother, a position both were driven to by a jealous patriarch. As the wicked father figure, Ian Kelly has a good go, but the “frightening presence” he is supposed to have cast over wife and son isn’t convincing – he is too sorry a figure to have caused much tension.

There’s a lot of RP accents and stiff upper lips (all delivered well) that raise smiles surely not intended by Storm. But that isn’t the big problem. The encounters between our nouveau klepto Alicia and her doctor, handled spryly enough by Nicholas Murchie, are focal points that prove myopic. A diagnosis of empty-nest syndrome is arrived at ridiculously quickly. Psychiatrists as all-seeing saviours may have been novel for Storm’s audience, but the idea just seems odd nowadays. A further twist, motivated by Alicia’s will to sacrifice herself for her family, comes as no surprise. It’s not so much an upper-middle-class obsession with privacy as the doctor’s admiration of such that seems silly.

Unless you’re particularly interested in post-war theatre Black Chiffon only has one big attraction: a star turn from Abigail Cruttenden in the lead role. She gives Alicia a dignity that’s believable and makes you care about the character. Better still, she is wonderfully natural; understated yet emotionally intense, with period touches kept under control. There are tricks here that many a performer in an historical drama could learn from and, although it’s a close call, Cruttenden makes the show worth seeing.

Until 12 October 2019

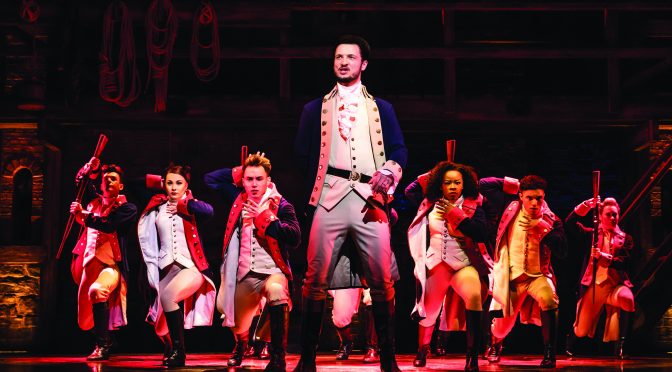

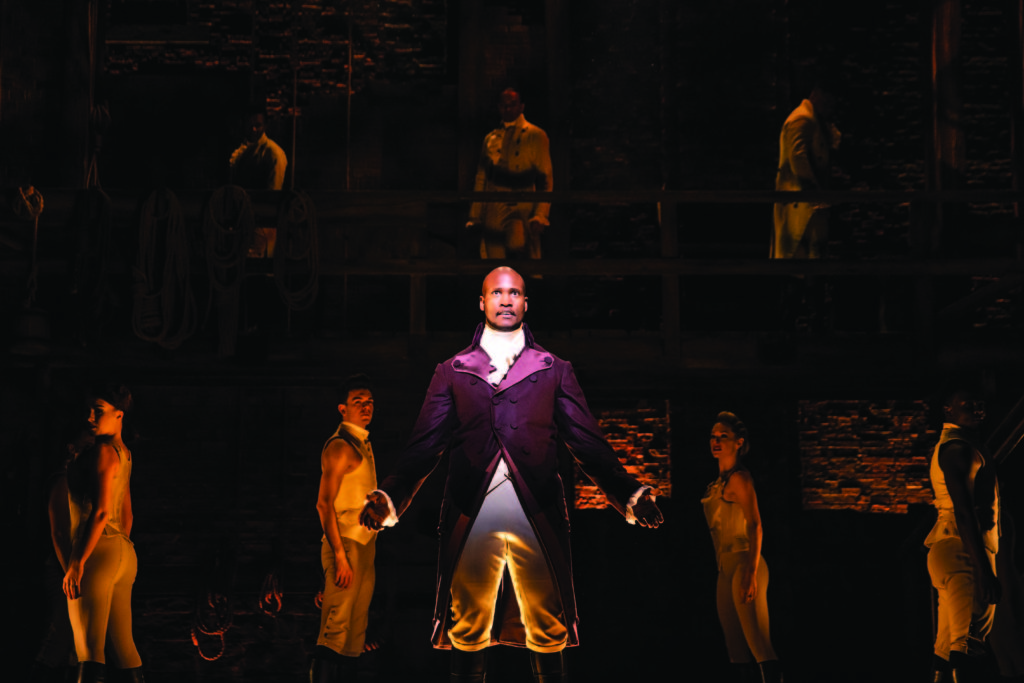

Photos by Mark Douet