Playwright Annie Baker’s first two outings on the Southbank made me a big fan. While The Flick and John were also concerned with storytelling, this third trip to London makes that topic even more explicit. As with the other plays, the setting is one room; this time a group of writers are trying to come up with ideas. Frustratingly, the scenario is never fully explained but as they brainstorm, telling seemingly random stories for inspiration, the play becomes obtuse and ends up a disappointment.

Led by Conleth Hill’s Sandy, some kind of studio guru who wants to create a “safe space” for ideas, there’s sharp satire on the creative industries, with some great observations on hierarchy in the workplace. And, as usual, Baker’s ear for contemporary voices is faultless. It’s a shame none of the characters we meet is someone we come to care about. Two old hands reveal intimate details just to shock (which leads to great performances from Arthur Darvill and Matt Bardock). Other recruits do less well: Stuart McQuarrie’s character, superbly performed, disappears after his tender personal history doesn’t impress. It all raises questions about creativity, pretty obviously. There are lots of discussions about formulas for stories that naturally interest writers – maybe audiences not so much? But Hollywood (or possibly the videogames business) isn’t really Baker’s aim…there’s more to come and The Antipodes gets increasingly confusing as a result.

The target is myths, the origin of storytelling, which takes us into dark territory. There’s much discussion of monsters and voids, but to what aim? Possibly Baker directing her own work, with the aid of Chloe Lamford, is too close to the project? The journey to explore all these themes is poorly handled, the results unconvincing. Take the forest fires that trap the protagonists at work – a too obvious attempt to create an apocalyptic air. As the writers continue failing in their aim to come up with new ideas – which in itself isn’t very interesting to watch – what’s going on becomes more bizarre. A scene performed by Bill Milner is the focal point here, but defies explication. It’s fine to abandon narrative structure (Milner’s character’s actions aren’t part of any plot) but expanding their thematic fit would be helpful. The tension Baker and Lamford create becomes both uncomfortable and uncanny. Top marks for atmosphere. But what the whole exercise is for becomes a puzzle.

Until 23 November 2019

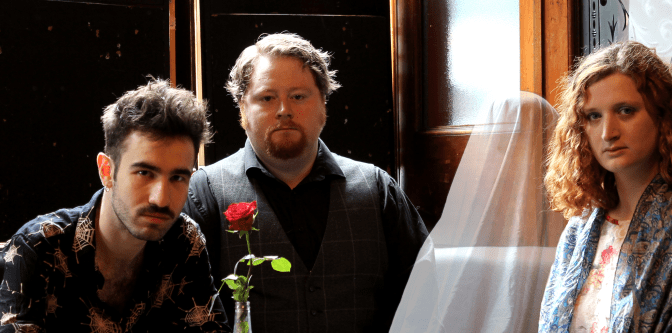

Photo by Manuel Harlan

![“[Blank]” at the Donmar Warehouse](https://onceaweektheatre.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/1.-The-company-in-BLANK-at-the-Donmar-Warehouse.-Director-Maria-Aberg-Designer-Rosie-Elnile.-Photo-Helen-Maybanks-157-1-672x372.jpg)