This trilogy of plays, marked by diversity and connected by a morbid streak, is an uneven but bold effort at very serious theatre for this Islington venue and its artistic director, Alexander Knott.

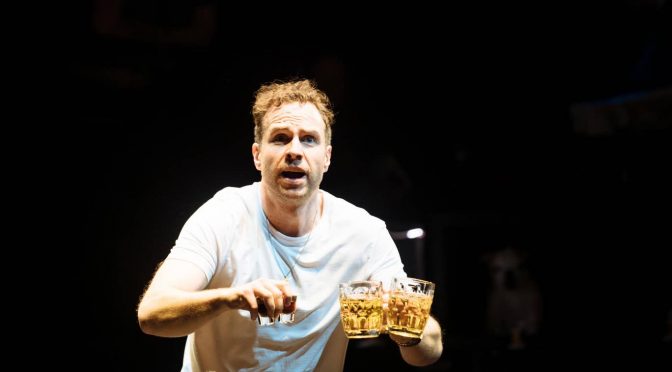

First up, Buried is the true story of the playwright David Spencer’s father, who was buried alive during World War II. And you do need to know that before you sit down. Presenting a stream of consciousness, recounting a tough life in horrific circumstances, the monologue ends up more confusing than powerful. The performance, by the subject’s grandson James Demaine, is impressive. With quick changes of accents and emotions, the skill is clear. Directors Knott and Ryan Hutton show considerable resourcefulness. But there’s an air of a talent showcase that creates a barrier to being involved in this powerful story.

Next is a short sketch, with a mention of war, by Max Saunders-Singer, that shows a teacher having a suicidal breakdown in his classroom. Anthony Cozens takes the role and does well with the audience participation that proves essential to the piece. But relying on the crowd to feed lines proves painful. Despite a firm hand from director Sonnie Beckett, the piece is unclear as to how serious it wants to be. And it’s in questionable taste. Some people don’t want to see a pornographic film projected in the theatre – no matter how blurred.

The lead attraction, thankfully, makes a superb finale. The first revival of Simon Stephens’ Nuclear War since its premiere at the Royal Court in 2017 reminds us of this exceptional piece. A meditation on grief and mindfulness, it takes in ideas theoretical, astronomical and balletic! Equally cerebral and earthy, it’s mind blowing and moving. Marked by experimentation and abstraction – in stark contrast to the others, which have plenty of biography – the emotion it engenders is remarkable. And the biggest praise is that I liked this production more than the original!

Knott’s decision to present a two-hander (Stephens doesn’t specify the number of performers) makes the action clearer, while retaining a fluid rhythm. Assisted by Lewie Watson, and with movement direction by Georgia Richardson, the precision and musicality of the text is brought out – a tap dancing section is quite brilliant. The performances, from Zoë Grain and Freya Sharp, are flawless. Often speaking in tandem and using the venue’s intimacy to great effect, this is expert work. It’s not a case of saving the show – the play makes up the bulk of the production – but Nuclear War is more than enough all on its own.

Until 21 March 2020

Photos by Charles Flint

![“La Cage aux Folles [The Play]” at the Park Theatre](https://onceaweektheatre.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/crop-Paul-Hunter-Albin-and-Michael-Matus-Georges-in-La-Cage-aux-Folles-The-Play-at-Park-Theatre.-Photo-by-Mark-Douet-1-672x372.jpg)