From Shakespeare in Love to Anthony Burgess’ excellent novel, A Dead Man in Deptford, William Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe make good source material. Playwright Liz Duffy Adams recognises the potential and puts them head to head in a fast, clever piece. If you like your history explored and exploded, this one is for you.

Quite rightly, Duffy Adams isn’t afraid to take liberties with facts (indeed, she points out that both Shakespeare and Marlowe did the same thing). She uses our lack of true knowledge about their lives wisely… they may indeed have worked together on the Henry VI plays, been gay, Catholic or, well, make your own case. And our prejudices about the men are exploited to great effect, with ideas about the brilliant but dangerous spy and occultist Marlowe contrasted with the Bard, who is mysterious or… just a bit boring? The contrast is funny and layers the show with éclat.

Such reputations are overplayed at times – fine for Marlowe but a little tiresome when it comes to Shakespeare. But Duffy Adams goes all in. The dialogue is bracing, with effective deadpan delivery, and a lot of it is rude! There’s a neat balance of period feel and references to the men’s work that, while plentiful, are not overwrought. Director Daniel Evans and designer Joanna Scotcher follow the text’s lead in being a little, shall we say, big. There are bold videos and loud music to introduce scenes.

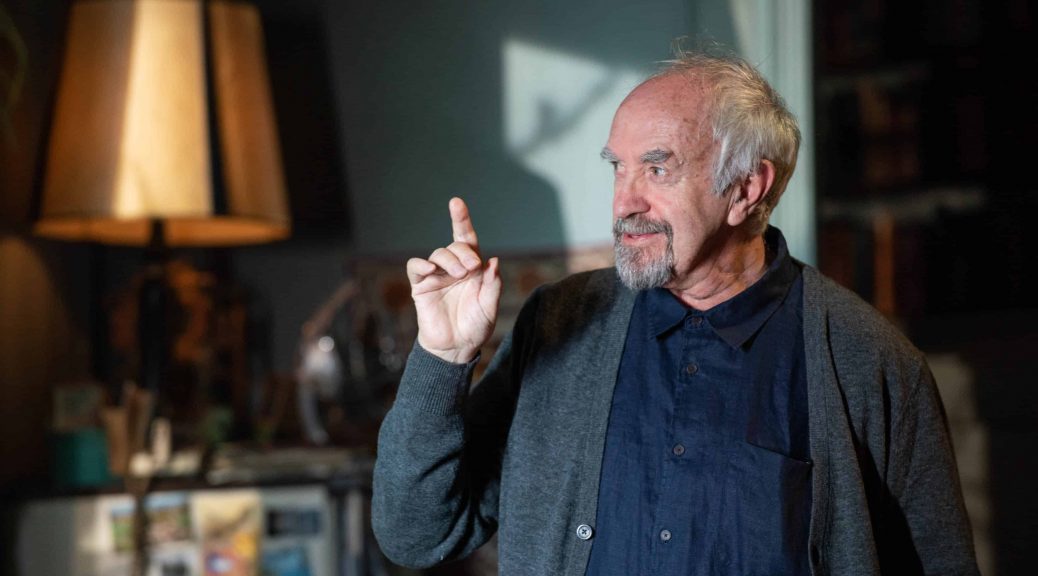

Performances are appropriately energetic (especially considering this is two men talking in a room) and downright sexy. The pace is embraced by both performers – Edward Bluemel and Ncuti Gatwa – who will, for many, be the production’s highlight.

Gatwa brings his usual charm to Marlowe, is fantastic with the show’s comedy and provides a passable air of danger. He is excellent when it comes to ego and Marlowe’s is presented as huge. There’s no doubting the stage presence – and how he works his extravagant quill is a sight to behold. As Shakespeare, Bluemel has the tougher task of suggesting depth and intrigue at first and then growing his role. He gets more time with us to try to make sure this works. Shakespeare introduces the scenes and keeps the theme of trust, in art and life, vivid.

A balance of sympathy, rivalry and attraction between the two men drives the show. But the action is small. For all the talk of espionage, a spy story this is not. The vague idea of having powerful friends and then having to betray people (for why?) doesn’t get going.

Because, as you’d expect, there’s more going on than speculation about two historical figures. Born With Teeth tries to show us two ways to live, two views of the world. There’s plenty of discussion about the men’s philosophies. But it’s heavy-handed and lacks clarity. Marlowe is Machiavellian and strangely resigned to his fate – much more is needed here. Shakespeare ends up an Enlightenment figure, precociously aware of literary theory. It’s interesting, if rushed. And if it’s not altogether convincing, it’s always entertaining.

Until 1 November 2025

Photos Johan Persson