Although it has a running time of only 45 minutes, there’s nothing little about this masterpiece from Caryl Churchill.

Believe it or not, despite the brief duration, Far Away could even be thought of as three plays rather than one. Maybe the scenes, despite shared character names, don’t have to be connected?

Churchill’s invention provides a trio of dystopian visions, each scary and increasingly bizarre, held in tense suspension with one another.

First there’s a trip to the proverbial woodshed, then a workshop producing hats for a judicial display. Finally, we see the world at war in a peculiar fashion. This is political turmoil that straddles allegorywith prescient fears in a unique fashion.

Of course, Churchill didn’t invent dystopian dramas, and she uses Orwellian overtones expertly. But it’s easy to see how influential this text from 2000 has already been. The mix of sci-fi with macabre touches means the play hasn’t dated a jot. And this production does the text proud.

Lizzie Clachan’s set combines simplicity with theatrical surprises. The sound design from Christopher Shutt will give you goose bumps without being ostentatious. And director Lyndsey Turner admirably resists the temptation to spin out the stories. The only extravagance is the use of supernumeraries, drawn from the Donmar’s ‘Take The Stage’ programme, who do a great job. But their appearance is brief. There’s a recurring theme here – a respect for Churchill’s marvellous economy.

Take the characters that we meet, so briefly and in such complex circumstances. Turner’s cast is superb in creating a sense of ordinary individuals no matter how removed from us the situations seem. Jessica Hynes, Aisling Loftus and Simon Manyonda provide just enough glimpses into the everyday lives of the roles they take. While appearing respectively as Harper, Joan and Todd twice, the characters change dramatically, revealing extraordinary skill from the actors and creating incredible tension. That such richness can come from such austerity really shouldn’t be possible! Churchill’s writing is breath taking – every line in Far Away works close to the bone.

Until 4 April 2020

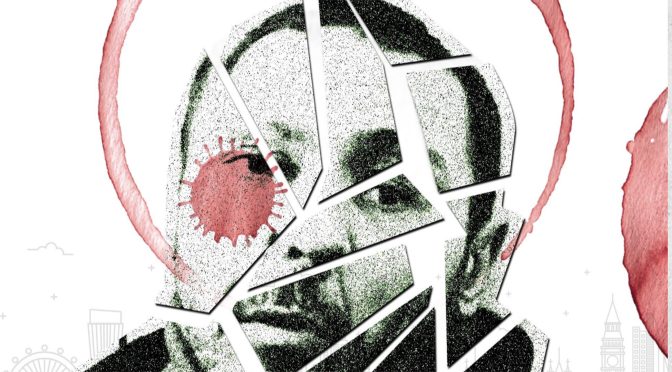

Photos by Johan Persson