Any production of a comedy at the National Theatre is likely to be compared to the venue’s most recent success, One Man, Two Guvnors. As Richard Bean’s updating of Goldoni’s play moves to Broadway, and opens with a new cast in the West End, the National’s newest attempt to make us merry is a traditional version of another 18th-century classic, Oliver Goldsmith’s She Stoops to Conquer. Remarkably, the National has succeeded again – this is a delightful production with guaranteed belly laughs.

Our hero Marlow is sent to visit his prospective bride Kate, played commendably by Harry Hadden-Paton and Katherine Kelly. But while Marlow can banter with barmaids he is impotent when flirting with women of his own class. A practical joke by Kate’s half-brother Tony Lumpkin (a superb comic creation in the hands of David Fynn) leads Marlow to believe the home of his future father-in-law is the local inn. Exploiting the confusion, Kate joins in the deception, bawdily stooping in class to conquer her diffident suitor.

Another pair of lovers, Constance (the appealing Cush Jumbo) and Hastings, joins the fun, planning to elope under the nose of the former’s guardian, the pretentious and avaricious Mrs Hardcastle. Sophie Thompson is superb in the role, her deliciously exaggerated performance making her one of the most endearing characters of the piece. But it’s John Heffernan as the foppish Hastings who takes the evening’s comic laurels delivering a master class in buffoonery and raillery.

It’s a relief that director Jamie Lloyd doesn’t try anything tricksy with the play. She stoops to conquer is “old-fashioned trumpery” that doesn’t need a modern take. Lloyd has the confidence to play it straight, knowing he just has to control the action, and the laughs will follow. Mark Thompson’s design provides the doors to slam – the text doesn’t really call for them but they add a reassuringly farcical touch. And the music – all pots and pans and trolololing, provided by Ben & Max Ringham, directed and arranged by David Shrubsole, adds immeasurably to the production. You have to see the ensemble perform it to believe how funny it is – that’s if you can hear it above the laughter.

Until 28 March 2012

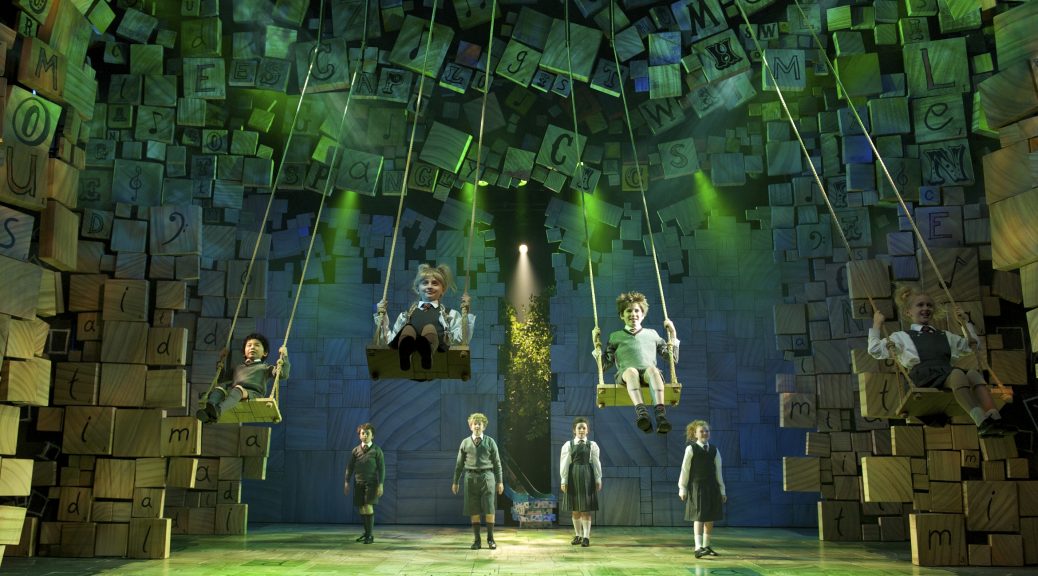

Photo by Johan Persson

Written 1 February 2012 for The London Magazine