This is the best production of a Tennessee Williams play I’ve seen. Director John Tiffany brings out the text’s peculiar humour and pathos while exploring its status as the author’s first ‘memory play’. A superb cast responds with style to this trilogy of achievements.

The memory play was an idea Williams explored throughout his career. This original effort, with our hero Tom recalling his life with the mother and sister he abandoned, is raw with autobiographical guilt. It is also highly poetic. Respecting this lyricism is one of the production’s fortes, mostly secured by Michael Esper’s beautiful delivery, as well as suggestions of movement, mime and dance aided by a score from Nico Muhly.

Bob Crowley’s design also complements the elegiac air: an Escher-style fire escape and pools of water might sound artsy but are understated. The set is a dreamlike, darkened bubble without walls, yet the claustrophobia of the two-by-four flat closes in on you. But there’s something comforting in that darkness as well, with a hint of masochistic pleasure in the nostalgia can.

The memories are those of Esper’s Tom. Fey, often funny, his guilt makes him a tragic figure, whose outbursts are tinged with a hysteria that Esper handles especially well, convincing us that he is living in a “nailed up coffin”. As a contrast, remembering how complex Williams’ heroines are, there is a magisterial performance from Cherry Jones as his dignified mother, Amanda, whose wit brings out the play’s lighter touches. After all, these lives have their high points – joy in reflecting on the past and fantasising about the future, with realistic fears adding a degree of tension. As “a woman of action as well as words”, this Amanda is someone to respect.

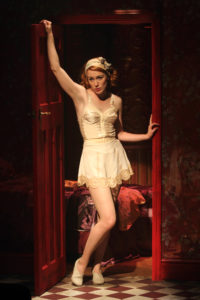

As for the production being emotionally potent, it is Briton Kate O’Flynn as fragile sister Laura and Brian J Smith with a tender portrayal of her gentleman caller who deliver the goods. Smith is heart breaking not just due to her innocence but because she has a wider awareness than her family credits her with.

Tiffany’s credentials are currently high due his work on Harry Potter. Famously in The Glass Menagerie, Tom claims he is a magician, but it is the whole cast and their director who deserve that title here. Conjuring the best out of each element of this masterpiece, they make the production enchanting.

Until 29 April 2017

Photos by Johan Persson