It would be a touch perverse, and thankfully difficult, to be uncharitable towards this new play. Based on the memoir by Ibrahima Balde and Amets Arzallus Antia, it tells the story of the former’s journey from Guinea to Europe. In contrast to the tendency to abstract and politicise the topic of immigration, this is a simple story showing life’s unexpected turns at a personal level.

Balde never intended to be an immigrant. His motivation is to search for his little brother, his journey even more shocking and dangerous than you might expect. Balde and Antia provide poetry, but the achievement in Timberlake Wertenbaker’s adaptation is to maintain an air of unvarnished truthfulness. The account is more than a documentary but it has a stark authenticity that makes belief unquestionable.

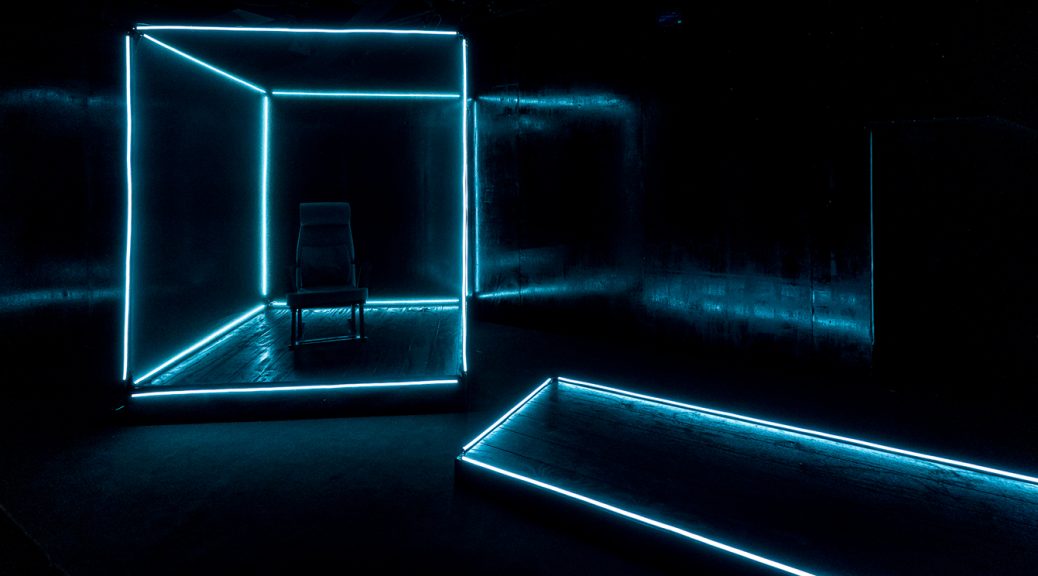

Director Stella Powell-Jones does a great job of bringing a story that covers so much time and space to the small stage of Jermyn Street Theatre. There are no fancy touches – they’d seem out of place – just a strong cast and subtle sounds from Falle Noike and Max Peppenheim. The performances are led by Blair Gyabaah, who barely leaves the stage for the 90-minute duration and is supported by Youness Bouzinab, Ivan Oyik, Mo Sesay and Whitney Kehinde, who take on the roles of everyone Balde meets. Kehinde works particularly hard as every woman and has many powerful scenes. For my taste, too much effort is taken to distinguish these different people (with costumes and characteristics) when it is what they do that seems to be the point here. Still, Powell-Jones generates considerable tension as we wonder how each will treat Balde, guessing or dreading whether their response will be good or bad.

Much of the journey is as grim as it gets. Balde is homeless, kidnapped, tortured and literally sold. The trauma from events is described articulately without being dwelt upon. And there is also a lightness to the show that is remarkable. The script, and Gyabaah, expertly tread a fine line, showing an acceptance of events without a resignation about them. Throughout, it is emphasised that the people met are like you and me, drawing the audience in and quietly interrogating us. And a lot the encounters are good. The acts of kindness, big and small, begrudging or unquestioned, pepper the journey. Charity is the key… and the challenge presented.

Until 21 June 2025

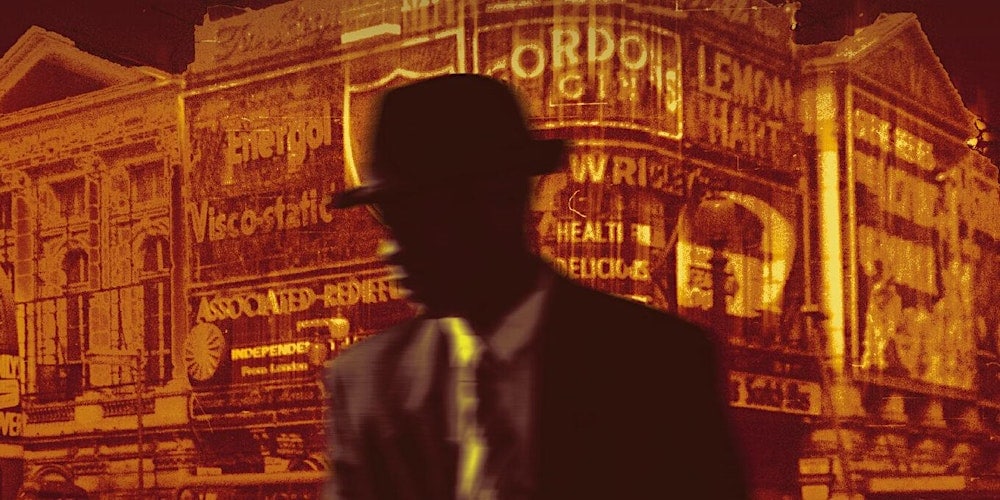

Photos by Steve Gregson