Of many exciting musicals opening in London this year – there are a lot – you might not expect this arrival from Australia to be a five-star favourite. The subject matter is the fandom surrounding a teenage boy band, and one young girl, Edna, with a plan to “save” the lead singer from his own celebrity when he tours to her town. So far, so fun. The show has its own dedicated following – there are Fangirls fan girls – because it really is for everyone: full of surprises, exceptionally smart and very funny.

The music, book, and lyrics are all by Yve Blake, which should make you ‘stan’ her. Blake is brave, not least in having the lead singer of her fictional boy band being a Brit called Harry. The show’s tone is boldly dark and downright rude. I’m not sure how suitable it is for youngsters, but that’s surely just me showing my own age! Of course, you laugh at reactions to the pop idol, the fans are “literally dead” at a concert announcement and there’s a mother character (a fantastic role for Debbie Kurup) for older audience members to relate to.

But hold on… don’t dismiss these “silly little girls”. The twist is that Fangirlstakes them seriously.

Blake has researched it all, creating an authentic voice for the show… literally. The lyrics are original, and the teenage speech patterns have fascinating effects. The plot has shocks, not least when Edna puts her plan into action (a fantastic end of the first act that I defy you to see coming). But there’s a point behind the technique. Through exploring the impact of the internet, the writing of fan fiction and the fan community, there’s insight into the lives and (unrequited) loves of this cohort that is frequently heartbreaking.

These girls’ self-esteem is fragile. The parasocial relationships with Harry, and their imaginary conversation with him, reveal fears and real-life difficulties in powerful lyrics. One number, ‘Disgusting’, is a highlight. As it happens, there’s an interesting parallel with another summer hit, Mean Girls, but, for my money, this packs more punch. As the group sings that “nobody loves you like me” (all of them, of course), the lyrics are shared by Edna’s mother singing to her daughter – their relationship is a big theme that gets ample attention.

“Actual philosophical poetry”

The score is just as clever. A concert from the boy band is a lot of fun, but it is clear from the start that the fictional hits are used in a novel way. Blake can write a pop song and Thomas Grant, who performs as Harry, does very well with them. But it is genius (and, again, funny) to make them a little bit bland. They are clearly a long way from the “actual philosophical poetry” one fan claims them to be. Then, when the fans take them over, adapting them and weaving them into the wider score, they are improved!

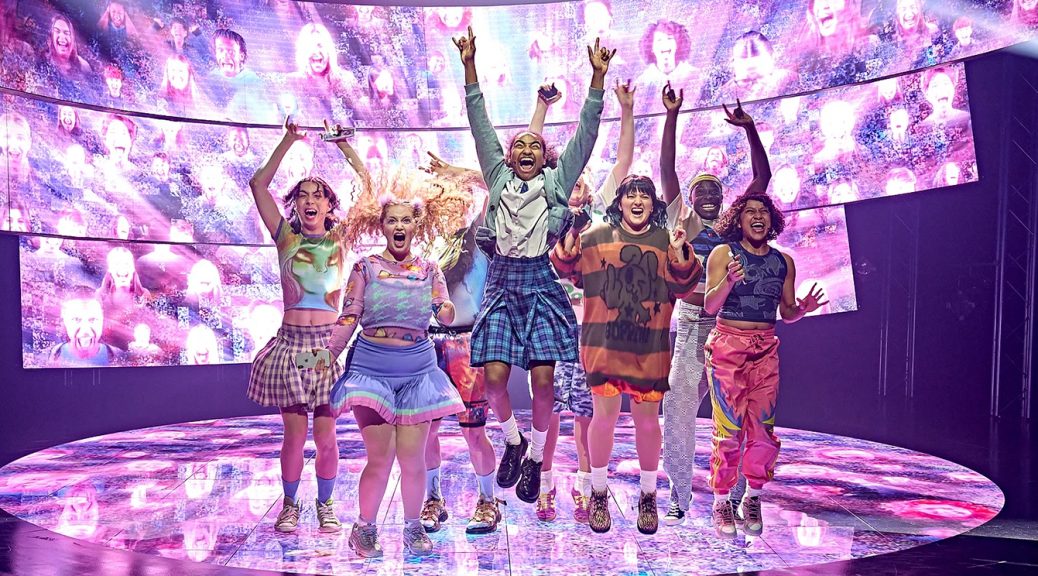

The fans as a chorus are utilised a lot and sound great. They move brilliantly, too, with clever suggestions of awkwardness around sexual or violent movements that show the skills of choreographer Ebony Williams. The production’s strength is a credit to director Paige Rattray. There are strong parts for Edna’s friends played by Miracle Chance and Mary Malone, but smaller roles are also well realised with standout performances from Terique Jarrett and Gracie McGonigal.

Final praise to Jasmine Elcock (a former talent-show competitor herself), who takes the lead role and is an excellent singer and actress with sure command of the show’s comedy and drama. Edna has a lot to learn and plenty of problems, so watching her struggle and grow is superb. And Elcock becomes a star along the way. What can say? I’m a fan.

Until 24 August 2024

Photo by Manuel Harlan