This trip to the summer of 2009, generously available during lockdown from globeplayer.tv, is a classy affair that is blissfully difficult to find fault with. Director Dominic Dromgoole’s production has plenty of traditional touches – including gorgeous period costumes from designer Simon Daw – a fresh appreciation of the text from a cracking cast, and a seemingly effortless handling that makes it easy to recommend.

Dromgoole’s skill is clear – he makes the play tight and concise without losing any nuance. There’s a dark undertone appropriate to the star-crossed lovers that shows “violent delights have violent ends”. Ian Redford’s excellent Capulet possesses a frightening anger, while his wife’s grief for their nephew Tybalt’s death makes a fine scene for Miranda Foster. Both render palpable the vendetta that exists in Verona, presided over by a bruiser of a Duke lifted from London’s East End (an excellent Andrew Vincent). A sense of excitement is aided by some of the best fight scenes I’ve seen – congratulations Malcolm Ranson on those.

Alongside this drama, Dromgoole brings out a gentle humour in Romeo and Juliet that feels distinct and is delivered without too much exaggeration. Jack Farthing’s Benvolio benefits most but there’s also a strong turn from Fergal McElherron as a crowd-pleasing servant and Tom Stuart’s hapless Paris is watchable and endearing. The wordplay that makes up so much of the text feels light and witty – something that we are welcome to enjoy rather than scratch our heads over.

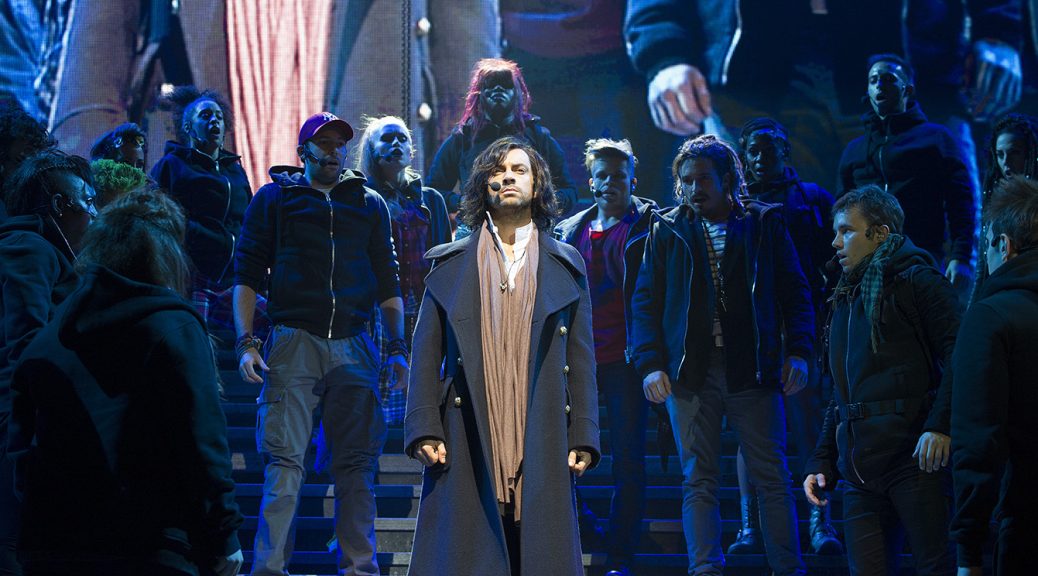

Ultimately, any production of Romeo and Juliet has to rely on its leads and this one benefits from a couple who gauge the tenor of the production perfectly. Adetomiwa Edun makes a charming Romeo and does especially well in showing how bright his character is. And there’s a dangerous edge; kicking Tybalt when he is down proves a startling move. Ellie Kendrick makes sure her Juliet is a “soft subject” for “Heaven’s stratagems”. Shy and modest until tragedy strikes, she ends up shaking with grief. Enforcing the youth of the couple proves effective. Dromgoole makes sure the action escalates as we see the youngsters trapped in events beyond their control. Excellent work from tense start to tragic finish, with a confidence that ensures, along the way, we come to care for and admire them both.

Photo by John Wildgoose

Available until 3 May 2020 on globeplayer.tv

To support visit www.shakespearesglobe.com