If you put three sisters at the heart of your play, as Beth Steel does, then your audience is likely to think of Chekhov. Add a community in some kind of decline (in this case, a former mining town) and a new group on the rise (here, Polish immigrants) and more bells ring. The comparisons prove interesting but might not be complimentary. Steel’s play is funny, but its humour isn’t subtle. There’s a lot of drama, but it often approaches soap opera. What impresses, though, is that the trio of siblings prove strong enough to stand on their own – powerful characterisation and excellent performances make the show.

We join Hazel, Maggie and Sylvia on the latter’s wedding day. There’s a lot of stress as well as fun, and it’s clear from the start these are fine roles for Lucy Black, Aisling Loftus and Sinéad Matthews, who all do a great job. Tensions in the family are skilfully revealed, with the women’s father, a cheating husband and a frustrated groom providing more strong turns from Alan Williams, Adrian Bower and Julian Kostov. The men aren’t as well written but, with trouble brewing because of the new groom being Polish and Hazel’s marriage breaking down, the play is action packed.

Steel has a lot of interests. It’s a shame that a sense of community, and its problems, aren’t conveyed in more depth. The sisters’ grief for their recently deceased mother is hazy, too, although Williams helps here. Much better is a concern for time and memory, highlighting the joys that make life worth living – a child playing with a toy, a recollection of shopping as a family or a moment in the rain. Director Bijan Sheibani stages these impeccably (with help from lighting designer Paule Constable), creating theatrical moments that lead to goosebumps.

Steel has further success with another character, the sisters’ aunt, a terrific comic creation that Dorothy Atkinson excels in – full of wit, wisdom and convincing depth. This wedding day is not a happy one as the final moment shows the family breaking up. If the plot here isn’t exactly a surprise, it’s handled with sensitivity and an impressively even hand. There are sensational touches including, perhaps, too many shouting matches. Yet Steel and Atkinson manage to get laughs in the darkest moments, balance excesses and shows the skill of all involved in a play that is interesting and entertaining.

Until 27 September 2025

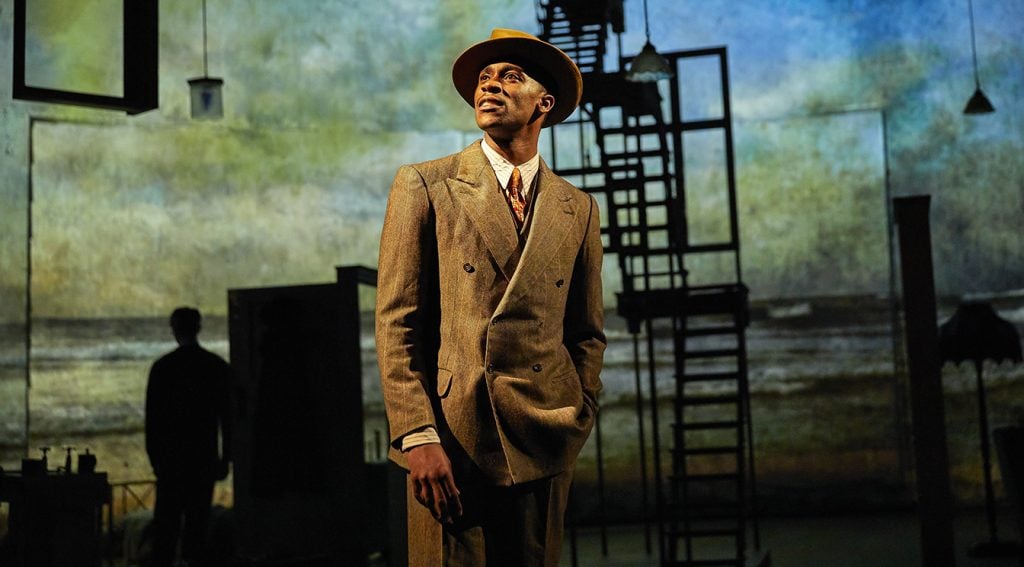

Photos by Manuel Harlan