James Corley’s new play brings a famous essay, a piece with a revered place in the Gay Liberation movement, to the stage with intelligence and style. We get the text and also the story of Merle Miller’s 1971 article for the New York Times, entitled ‘What it means to be a homosexual’. Corley has Miller present the prose while taking the audience behind the scenes.

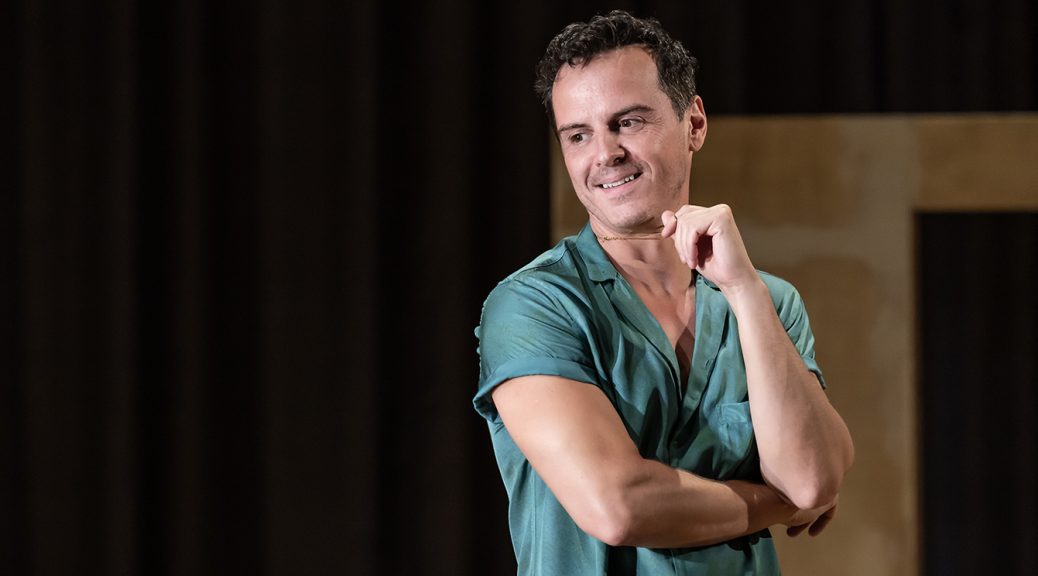

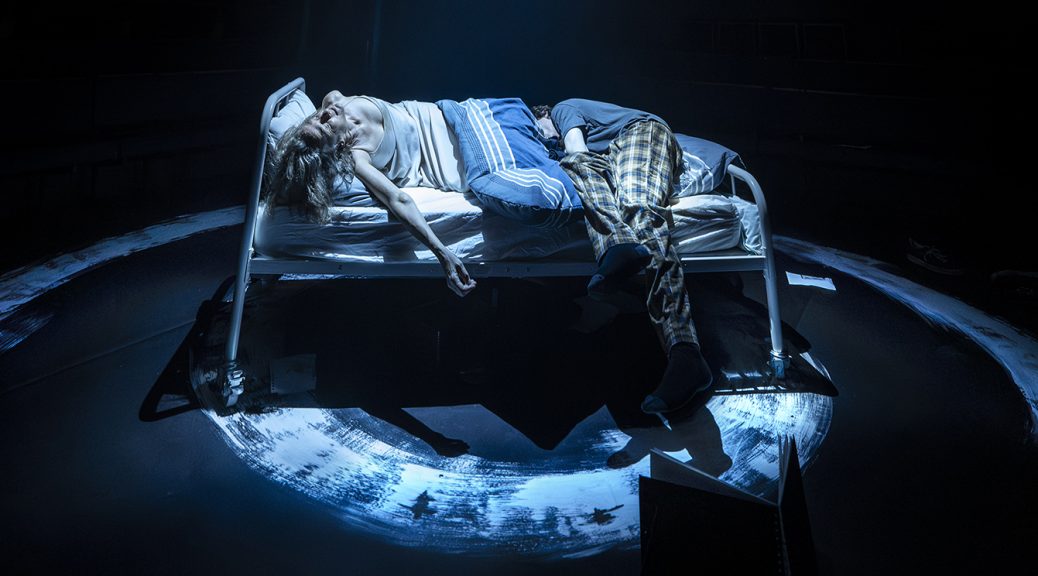

The biographical route makes sense. Not only was the essay personal but focusing on Merle – the man – makes the evening moving and funny. We learn that his coming out was slow and painful but, also, what a wit Miller was. And the strategy leads to an incredible performance from Richard Cant, who moves from raw emotion to dry observation and makes the show worth seeing for his performance alone.

The adaptation is full of interest, energetically directed by Harry Mackrill. Presenting to the audience sometimes confrontationally, the convivial tone has surprising tension as the action flits across time in a brilliant fashion. Showing the impact of painful moments in Merle’s past might seem a touch contemporary. But how his closeted status pervaded every aspect of his life is deeply moving.

A final section is the play’s finest… It’s a surprise to find that What It Means is not a one-man show.

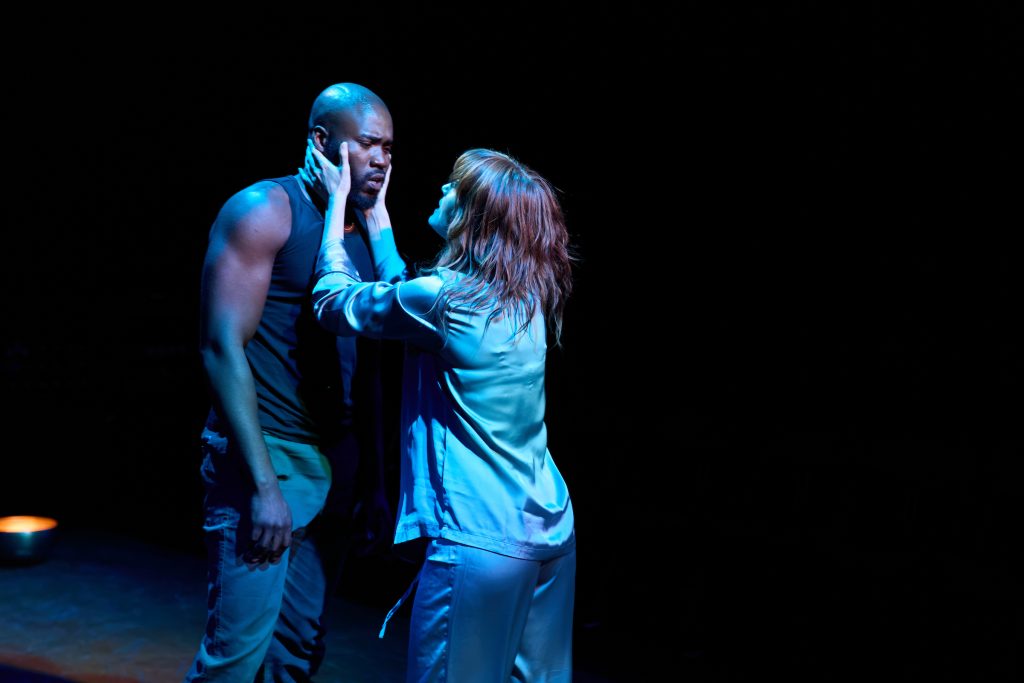

The appearance of Cayvan Coates, in a small role as a troubled youth, is inspired by one of the many letters that the article provoked. Coates makes an entrance via the audience so that, although the character is from Miller’s own day, the connection feels immediate. The character needs help and he needs it now.

Miller is aware he had no role models – no representation, as they say nowadays. But doesn’t the play itself provide just that? Like its source material, What It Means becomes a kind of activism. Having Miller still serve as an inspiration is a fine way to celebrate his legacy, and it is a neat move that makes the play is a fitting tribute.

Until 28 October 2023

Photos by Danny Kaan