A world première from Martin Sherman, directed by Sean Mathias, counts as a coup for this North London venue. The 80-year-old playwright’s latest piece is a careful meditation on age and, through the prism of an older artist’s affair with a young man, gives us a little gay history that ripples out to touch the most profound human experiences. It is crisp, rich and wonderfully well written.

In Beau, an older gentleman from the Southern States who becomes our hero, Sherman has written a great creation. Recognisable yet full of surprises and depth, he makes a great role for Jonathan Hyde. A series of beautifully written monologues about Beau’s life make the play worth watching all on their own. In a sense, these are all ‘war stories’, as a personal history that starts before World War II follows the course of gay rights. Sherman’s skill and Mathias’ tactful handling of these scenes banish any sense of them as contrived and Hyde gives a performance of great tenderness and subtlety. Careful about exaggerating any stereotypical touches, Hyde’s is a truly great performance.

We’re on less sure ground with the play’s younger characters. Rufus, who starts an affair with Beau, suffers from bi-polar disorder so a ‘manic energy’ is called for. But discussion of his health, which should be a central concern – mental health is a major issue among young gay men – is shied away from. Rufus’ next partner is a ‘performance artist’ and even less well defined. The idea behind his occupation is clearly to form a sense of legacy between gay artists, but it ends up just being a source of humour. Ben Allen and Harry Lawtey try hard in both roles, and they make them engaging, but the idealised friendship that develops pushes credibility too far and the jokes about youth seem too carefully planned. Ultimately, the other two characters pale next to the gloriously vivid Beau.

A “thirst for the past” exhibited by both young men shouldn’t be the surprise it is to Beau. History, a form of self-narrative, can surely be added to the list of things people need and seek. Theatre testifies to and answers this search. A close, recent, parallel is Matthew Lopez’s masterpiece The Inheritance. The works make for an interesting compare-and-contrast that, for most, will focus on duration. Sherman packs almost as much into his hour and half as Lopez does in nearly seven. A sense of urgency in the writing is balanced by Mathias’ steady hand, so not a moment feels rushed. And there’s a lot less misery here – more a sense of hope that comes from experience and a wry eye. Maybe wisdom provokes brevity as much as wit? Sherman is clearly gifted with all three qualities.

Until 16 March 2019

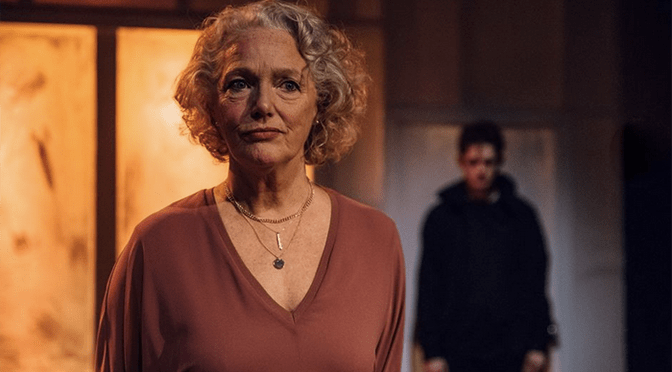

Photo by Marc Brenner